Finding the Reasons Why: Looking for Answers in Trends of Child and Youth Suicides

Finding the Reasons Why: Looking for Answers in Trends of Child and Youth Suicides https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Suicide-header-1024x575.jpg 1024 575 Kevin Mayhood Kevin Mayhood https://secure.gravatar.com/avatar/bd57a8b155725b653da0c499ae1bf402?s=96&d=mm&r=g- October 10, 2019

- Kevin Mayhood

Epidemiological studies are the first step to learn how to prevent suicide attempts and deaths.

Suicide is the second-leading cause of death among 10- to 24-year-olds. And even as awareness grows, the suicide rate continues to climb, according to national statistics. But those national statistics don’t tell the whole story. For decades, researchers around the country have been digging into the available data to look for patterns that could help them understand why so many youth continue to be affected.

At the Center for Suicide Prevention and Research in the Abigail Wexner Research Institute (AWRI) at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, this search has led to several papers revealing unique patterns in suicide for specific populations of children and young adults. The researchers have uncovered differences based on age, sex, race and more, and they are using the findings as a first step toward developing prevention strategies.

“If we can identify a pattern, if the epidemiology of suicide has changed over time and rates are increasing…these descriptive papers allow us to start asking what are some of the factors that might have changed that are driving the increase,” says Jeff Bridge, PhD, an epidemiologist, director of the Center for Suicide Prevention and Research in the AWRI and author of many suicide-epidemiology publications. “That allows us to home in on potential mechanisms that we or others might be able to target.”

USING SCIENCE TO DRIVE CHANGE

From small hospital-based research to deep dives in national databases, these studies have helped reveal vulnerable populations and challenge generally-held beliefs.

One notable study was published in May 2019, in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. The team at Nationwide Children’s was among several to investigate, and the first to publish their results on, whether or not the Netflix series “13 Reasons Why” could be linked to increased suicides. And what they found was compelling.

“We discovered in our analysis of national suicide rates that in the months following the release of the first season, suicides among youth aged 10-17 years increased by almost 30%,” says Dr. Bridge.

Following the “13 Reasons Why” study, Netflix removed the graphic suicide scene aired during the first season, saying it was “mindful about the ongoing debate around the show” and based on advice from medical experts.

“We hope that the actions taken, based on the evidence provided, are a proof of concept for how taking action to reverse trends where a clear association has been established can help save lives,” says John Ackerman, PhD, suicide prevention coordinator at the Center for Suicide Prevention and Research, and a co-author of the study.

“We have the opportunity to reduce the number of young people that die by suicide and the media certainly can play a role in that effort,” says Dr. Ackerman. “Contagion is a real concern when it comes to reporting about deaths by suicide and suicide research.”

To try to prevent suicide contagion – a process in which the suicide of one person or multiple people can contribute to a rise in suicidal behaviors among others – from media exposure, Dr. Ackerman worked with the E. W. Scripps School of Journalism at Ohio University and numerous suicide prevention collaborators to update guidelines on reporting suicide in traditional and on social media. The American Association of Suicidology not only supported this effort but adopted the guidelines this year as part of a media partnership toolkit.

The “13 Reasons Why” study is among six in the last year in which AWRI researchers have identified and studied subpopulations of youth who have attempted suicide or died by suicide, and the majority of the studies have shown an increase among youth is present.

A NARROWING GENDER GAP

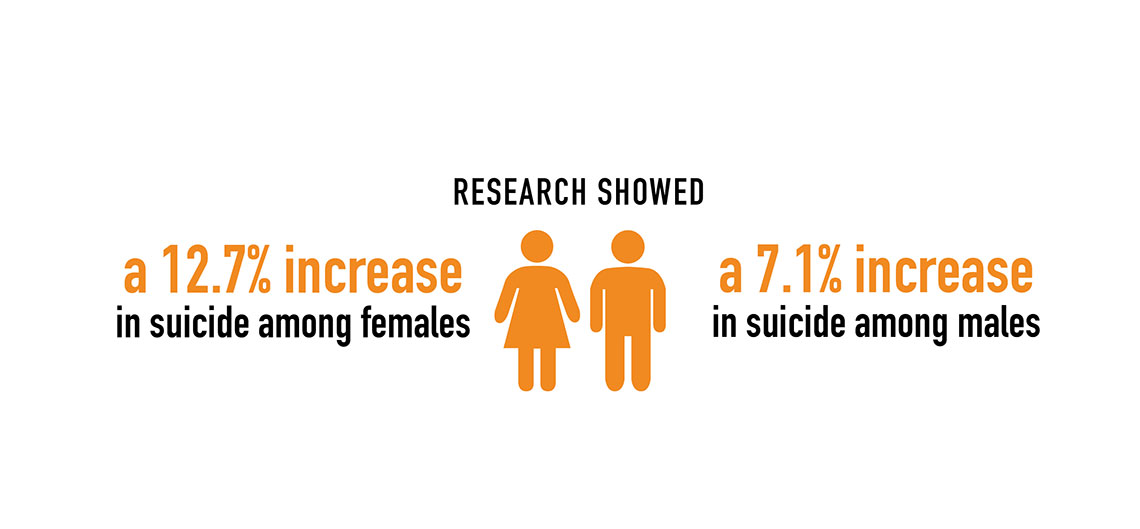

Among the alarming trends uncovered in the past year is the decreasing gap between the number of suicides among boys and girls, as reported in JAMA Network Open.

Historically, girls have more suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts than boys, but boys use more lethal means and die more often by suicide.

“Overall, we found a disproportionate increase in female youth suicide rates compared to males,” says Donna Ruch, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the Center for Suicide Prevention and Research and lead author on the study.

Her analysis of youth suicide from 2007 to 2016 from the Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiological Research records showed a 12.7% increase among girls ages 10 to 14, however for boys, the increase was 7.1%. The rate among girls 15 to 19 rose 7.9%, and for boys 3.5%. The study also found that rates of hanging and suffocation by girls is also approaching that of boys.

In another study, published in The Journal of Pediatrics, Henry Spiller, MS, D.ABAT, director of the Central Ohio Poison Center at Nationwide Children’s, and Dr. Ackerman found suicide attempts by self-poisoning more than doubled among 10-to 19-year-olds from 2011 to 2018, using data from the National Poison Data System. Among 10 to 15 year old girls, the rate more than tripled.

“The data is stunning…attempts were flat from 1990 to 2010-2011, then there was a significant increase that didn’t stop,” Dr. Spiller says.

“We can’t answer ‘why?’ from the available data, but this sharp increase in self-poisonings is being driven by girls at increasingly younger ages and the attempts are more severe,” Dr. Ackerman says.

REVEALING AGE-RELATED RACIAL DISPARITIES

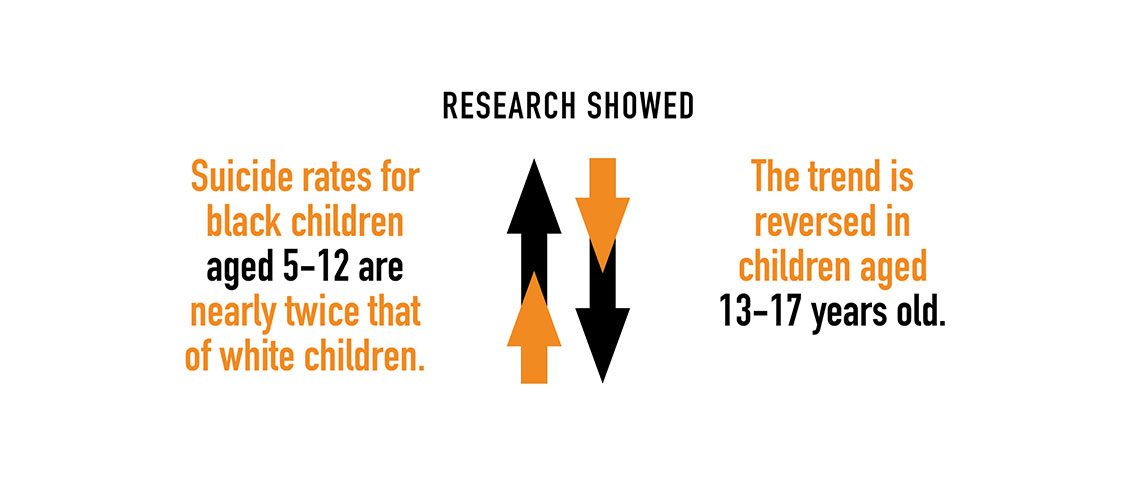

When looking at suicides by race, reported suicide rates had consistently been higher for whites of all ages than for blacks. But that’s not the whole story.

The Nationwide Children’s research team’s deeper look into Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data from 2001-2015 uncovered age-related racial disparity.

Suicide rates for black children ages 5 to 12, they reported in JAMA Pediatrics, are nearly twice that of white children. The trend is reversed in children 13 to 17.

“While we lacked information on key factors that may underlie racial differences in suicide, including access to culturally acceptable behavioral health care or the potential role of death due to homicide among older black youth as a competing risk for suicide in this subgroup, the results are illuminating,” says Dr. Bridge. “However, it will require additional studies to find out whether risk and protective factors identified in studies of primarily white adolescent suicides are associated with suicide in black youth and how these factors change throughout childhood and adolescence.”

Leading the charge on several of those studies is Arielle Sheftall, PhD, a principal investigator in the Center for Suicide Prevention and Research.

“We’re looking at trajectories of suicidal ideation and behavior and trying to identify early intervention opportunities,” she says.

Dr. Sheftall, who is a member of the work group providing education to the Congressional Black Caucus Task Force on Black Youth Suicide and Mental Health, and her team members at Nationwide Children’s are now looking at what makes black children under 12 more apt to die by suicide than young white children. Among several factors, she’s studying emotion regulation/reactivity and neurocognitive functioning, familial cohesiveness and adaptability, and parenting style. The team will examine how these risk and protective factors may vary by race.

YOUNG CHILDREN AT RISK

A myth persists that young children don’t plan or attempt suicide, the researchers say. But in a recent study, screening for suicidal thoughts and behaviors revealed that 7% of 10-to-12-year-olds who came to three children’s hospital emergency departments for medical complaints such as headache, back pain or seizures were at risk for suicide.

More than half of children in the same age group presenting to the emergency department with psychiatric complaints such as depression, violent behavior or panic disorder screened positive for suicide risk.

“In this study, we uncovered risk,” says Dr. Bridge, who is also a professor of Pediatrics, Psychiatry, and Behavioral Health at The Ohio State University College of Medicine. “Most of these kids come to the emergency department for medical complaints, not because they are thinking about or have attempted suicide.”

The suicide prevention team at Nationwide Children’s, which has worked with 125 high schools and middle schools, has also expanded training to staff in elementary schools, to help them recognize children at risk and know what steps to take to keep them protected. The team is in the early stages of developing a specific curriculum for 4th and 5th graders, to help them recognize when their peers or they themselves show signs of unusual unhappiness or stress, and to tell a trusted adult.

Nationwide Children’s Emergency Department and the Big Lots Behavioral Health Services now screen all children as young as 10 for suicide risk. Dr. Bridge and colleagues are developing a screening tool and intervention protocols that can be used in all medical settings.

RISK ASSOCIATED WITH JUVENILE DETENTION

Studies by others have sometimes provided the team a target to investigate. When a U.S. Department of Justice Survey showed incarcerated youth commit suicide two to three times more often than the general population, Dr. Ruch led a comparative analysis using data from the National Violent Death Reporting System.

The investigation, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, showed no significant difference in history of suicide attempts, mental health issues or other traditional risk factors exists between those who killed themselves in juvenile facilities and those outside.

“Youth who were incarcerated and died by suicide were no more likely to have mental health conditions than those who died by suicide in the community,” Dr. Ruch says. “That surprised us. And that led us to question whether there may be something about the environment that contributed to the increase in suicides.”

She suggests that the immediate shock of confinement and disruption to a youth’s regular life can be traumatic and increase the risk for suicidal behavior, especially for incarcerated youth with existing risk factors.

TAKING ACTION TO IMPROVE PREVENTION EFFORTS

For most of the studies, the researchers are now investigating what increases suicidal behavior in each of the identified populations.

They already found the increase is not associated with the 2007-2009 financial crisis or the opioid crisis. They suspect it has to do with the spread of smartphones, increasing screen time and the reach of social media around the clock.

“We’re looking for solutions – there won’t be a one size fits all answer for all of these populations,” says Dr. Bridge.

Ongoing prevention efforts include expanding access to behavioral health care, reducing stigmas for mental health conditions and suicide, and better equipping primary care providers, families and schools to help children in need.

“It never hurts to ask if a child or young adult is thinking about suicide,” emphasizes Dr. Bridge. “I say it in every interview – asking won’t hurt. It can only help.”

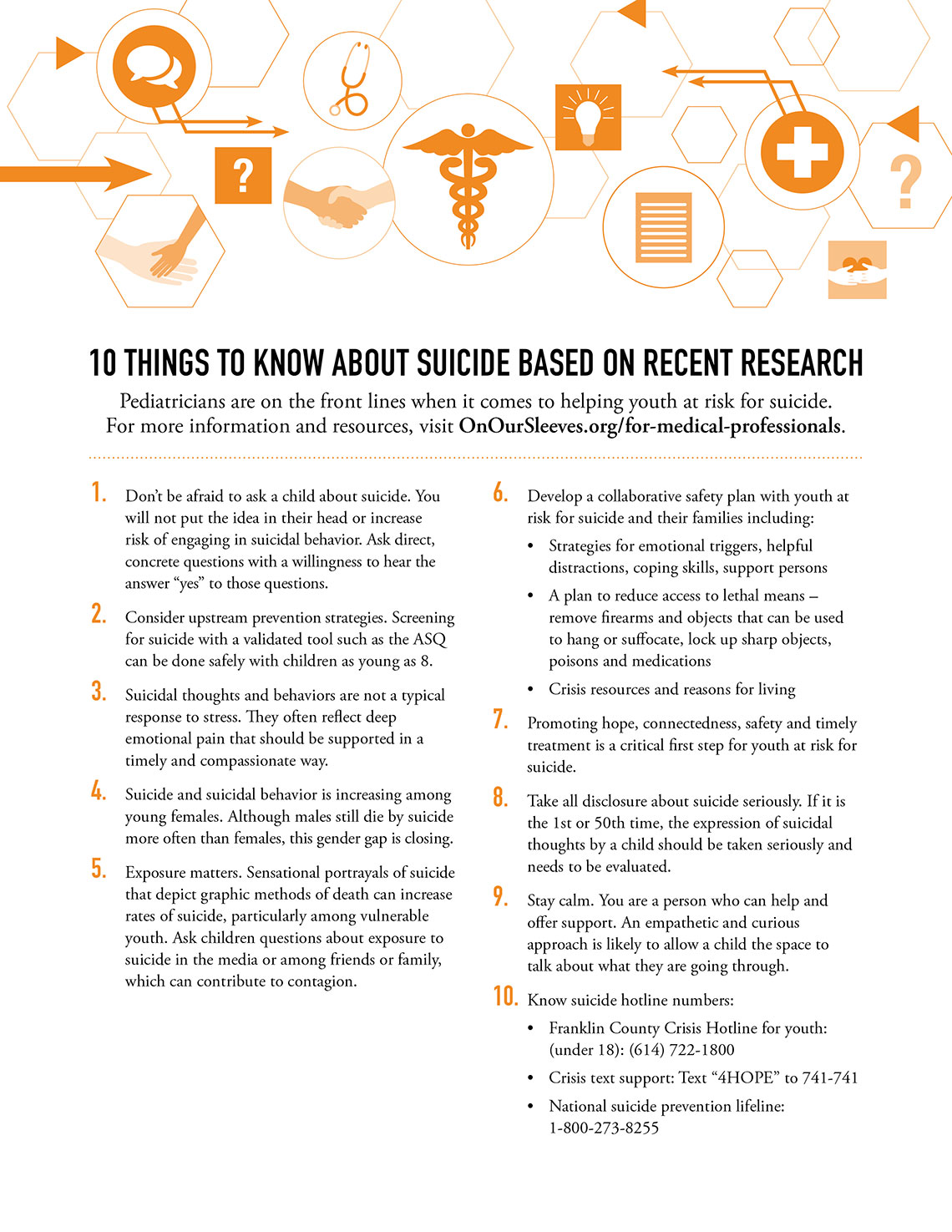

Get the 10 things you need to know about youth suicide based on the latest research as a downloadable and printable resource.

DownloadGET HELP NOW:

If you need immediate help due to having suicidal thoughts, go to your local emergency room immediately, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or reach out to the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741-741.

References:

- Bridge JA, Greenhouse JB, Ruch D, Stevens J, Ackerman J, Sheftall AH, Horowitz LM, Kelleher KJ, Campo JV. Association between the release of Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why and suicide rates in the United States: an interrupted times series analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2019 Apr 28. [Epub ahead of print]

- Ruch DA, Sheftall AH, Schlagbaum P, Rausch J, Campo JV, Bridge JA. Trends in suicide among youth aged 10 to 19 years in the United States, 1975-2016. JAMA Network Open. 2019 May 3;2(5):e193886.

- Spiller HA, Ackerman JP, Spiller NE, Casavant MJ. Sex-and age-specific increases in suicide attempts by self-poisoning in the United States among youth and young adults from 2000 to 2018. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2019 Jul;210:201-208.

- Bridge JA, Horowitz LM, Fontanella CA, Sheftall AH, Greenhouse J., Kelleher KJ, Campo JV. Agerelated racial disparity in suicide rates among US youths from 2001 through 2015. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Jul 1;172(7):697-699.

- Lanzillo EC, Horowitz LM, Wharff EA, Sheftall AH, Pao M, Bridge JA. The importance of screening preteens for suicide risk in the emergency department. Hospital Pediatrics. 2019 Apr;9(4):305-307.

- Ruch DA, Sheftall AH, Schlagbaum P, Fontanella CA, Campo JV, Bridge JA. Characteristics and precipitating circumstances of suicide among incarcerated youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2019 May;58(5):514-524.e1.

Image credits: Nationwide Children’s

About the author

-

Kevin Mayhoodhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/kevin-mayhood/

-

Kevin Mayhoodhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/kevin-mayhood/April 25, 2015

-

Kevin Mayhoodhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/kevin-mayhood/April 25, 2015

-

Kevin Mayhoodhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/kevin-mayhood/April 25, 2015