Best Practices for Research Recruitment and Retention

Best Practices for Research Recruitment and Retention https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Hallarn-Wentzel-header-1024x575.gif 1024 575 Tiasha Letostak, PhD Tiasha Letostak, PhD https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Tiasha-Letostak.jpg- October 18, 2016

- Tiasha Letostak, PhD

You can’t obtain study data without participants. From initial design and promotion to communication tactics and patient satisfaction, here are some strategies to ensure success.

Advancing pediatric research depends on successful recruitment and retention of study participants. Unfortunately, 9 out of 10 trials end up having to double their original timelines in order to meet enrollment goals, while 48 percent of sites under-enroll study volunteers. Finding enough of the right participants – and keeping them – is often the most difficult and challenging aspect of conducting a study.

“Most people do have an altruistic nature, so they want to help with research,” says Grace Wentzel, CCRP, director of Clinical Research Services at Nationwide Children’s Hospital (pictured on the left). “However, statistics show that we do a poor job of educating the public about why clinical research is important in the first place and of driving them to resources for finding those studies.”

Data from the Center for Information and Study on Clinical Research Participation (CISCRP) prove Wentzel’s points, revealing that 87 percent of the public are willing to participate in a study. Their reasons for doing so are to advance medicine (33%) or to help improve the lives of others (29%), rather than to improve their own condition (15%) or earn extra money (5%).

But a lack of general knowledge about research, combined with fears about side effects or risks to overall health, does keep individuals from enrolling. Twenty-six percent of the public doesn’t even know where trials are conducted, and after a study ends, 88 percent of patients rarely or never talk with others about research.

“The value of a study coordinator cannot be overstated,” says Rose Hallarn, director of the Participant Recruitment and Retention Program at The Ohio State University Center for Clinical and Translational Science (pictured on the right). “When someone is not eligible for a study, it’s really important that the coordinator selects the right words to explain to them why they’re not eligible, thanks them for their interest in the study and connects them to other available or ongoing studies. If someone is found to be ineligible for a study and isn’t redirected to another study or to other ways to find studies, almost 70 percent of them will never search for another one.”

So, how do you garner interest in the first place?

“Recruitment strategies can range from just a flyer in the clinic or an online ad to a doctor directly talking to a patient,” says Wentzel. “The key is to meet early with someone who will help you, preferably at least monthly, to dissect what’s working and not working, because you have to be willing to change your strategy and to have that flexibility built into your study recruitment plan.

The more upfront time you put into your plan, the more time you will save on the implementation side – for every hour of planning that you do, you will save 10 hours of actual work.”

According to the CISCRP, the public is most likely to obtain clinical research information online (46%), through the media (39%) or via email (32%). Both directors advise research teams to be able to succinctly convey the significance of the study in one sentence for any print or online advertisement. This includes why the study is important and why people should want to participate. Research teams should design marketing materials in a way that the general public will understand and effectively demonstrate the significance of the study to potential participants and their families.

“Our experiences have shown that large deviations from the standard of care and exposure to many invasive procedures will negatively impact your recruitment efforts,” says Wentzel. “Scientifically, the study may be rigorous – 14 blood draws or a number of invasive procedures – but it will be very difficult to recruit participants. If we can meet with a researcher early on, before the final study design is complete, we can assist in cutting down on the number of procedures or study visits to make it easier to participate, while ensuring that the study still meets scientific needs.”

Hallarn echoes this sentiment. “The participant is the most important member of the study team, and if the participant burden is too high, then you have no study. Think about how your study design may change the number of people who would be willing and able to participate in your study.”

Another aspect of study design involves identifying the best settings for recruitment, which may not always be a clinical setting when it comes to pediatric research.

Another aspect of study design involves identifying the best settings for recruitment, which may not always be a clinical setting when it comes to pediatric research.

“What is the standard of care for your study population, and where are they normally seen?” says Wentzel. “For example, if you were looking for healthy children under two years of age, you would find them in daycares.

When studying a particular condition, you can look at what procedures you’re doing that mirror what clinicians are doing elsewhere or where that patient population is already being seen, so you can try to take advantage of that existing standard of care.”

Other recommendations for recruitment include tapping into advocacy groups, either in-person, online or through social media. This might include patient-family conferences or Facebook groups for specific rare diseases. And using a national volunteer registry, such as ResearchMatch, or a universitysponsored site, such as StudySearch, can also assist you in reaching your intended study population.

“Depending on your population, knowing how they communicate matters,” says Wentzel. “If you’re trying to recruit teenagers or young adults – who don’t answer their phone or always check emails – using other methods such as texting, and getting approval to use that method, is crucial.”

Making sure that you include all potential communication options in your IRB application, explains Hallarn, will save valuable time, so you don’t have to go back and get these methods approved. “You may not think that you need all of these things, but get it approved. Then, if your initial recruitment strategies don’t work out, you don’t have to recreate your plan.”

Both Wentzel and Hallarn agree that choosing the right participants in the first place is essential not only for recruitment but also for retention.

“If patients are no-shows or noncompliant with clinic visits, then they are highly likely to be no-shows or noncompliant with research visits,” explains Wentzel. “These types of participants will likely adversely affect your research data and outcomes, unless it’s a single visit study. If you’re expecting someone to be in your study for 6 months, 12 months, etc., then you will want to recruit someone who has a history of being compliant with their visits.”

And what many investigators may not realize, says Hallarn, is that retention actually begins at the very first moment that a potential participant hears anything about your study or contacts you.

“If your response time is not within 24 hours, you lose about 67 percent of your potential participants,” Hallarn emphasizes. “And they already begin to feel that this might not be a place that they can trust.”

“I think what’s important for both recruitment and retention is to really establish a rapport with these families,” adds Wentzel. “Make sure they feel important, that we’re responsive to them and their calls, that their visits are good experiences and that they don’t have extensive wait times. It cannot be a hassle; their research experience needs to be enjoyable. Because, unlike care, they don’t have to be here.”

Efforts to retain participants by taking care of and anticipating their needs are akin to providing customer service, say Hallarn and Wentzel, because once a family has a good experience with research, chances are that the family will participate in other studies and recommend that others participate as well. The data reveals this trend, with the CISCRP demonstrating that 95 percent of participants would consider enrolling in another study.

Multiple factors can influence a research participant’s decision to drop out of a study. Although some dropouts are inevitable and due to factors outside of the research team’s control, many of these can be prevented.

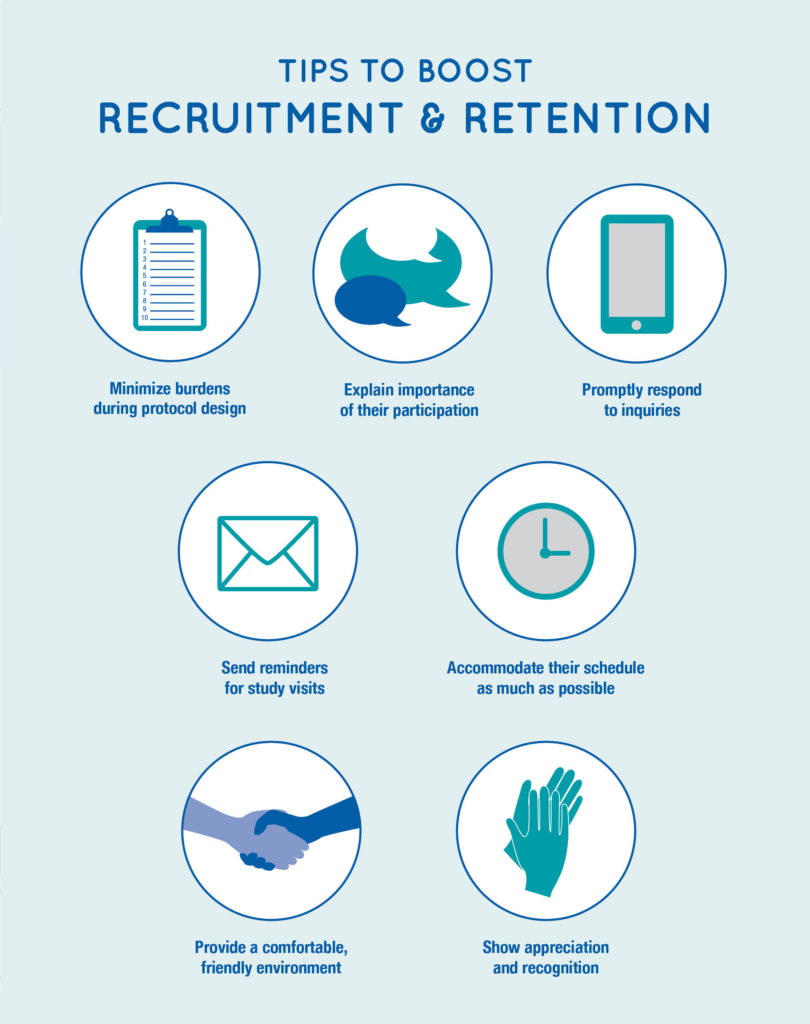

Minimizing participant burden during protocol design, explaining the importance of their involvement, and clearly communicating expectations upfront during the informed consent form discussion, are all actions that can be taken early on during the recruitment stage.

Retention can be augmented by promptly responding to inquiries, sending reminders for upcoming visits, showing appreciation and recognition, and accommodating participants’ schedules as much as possible.

Considering participants’ needs in all aspects of the study will enhance the experience of participants and their families, increasing the likelihood of enrollment in future studies and the likelihood of recommending that others participate in research as well.

References:

- Lopienski K. Patient Recruitment and Enrollment in Clinical Trials [Infographic]. Forte. 2014 Sep 11.

- Lopienski K. Retention in Clinical Trials – Keeping Patients on Protocols [Infographic]. Forte. 2015 Jun 1.

Image credit: Nationwide Children’s

About the author

Tiasha is the senior strategist for Clinical & Research Communications at Nationwide Children's Hospital. She provides assistance to investigators in The Research Institute and clinician-scientists at Nationwide Children’s for internal and external communication of clinical studies, peer-reviewed journal articles, grant awards and research news. She is also the editor-in-chief for Research Now, Nationwide Children's monthly, all-employee e-newsletter for research, as well as a writer for Pediatrics Nationwide.

-

Tiasha Letostak, PhDhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/tiasha-letostak-phd/

-

Tiasha Letostak, PhDhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/tiasha-letostak-phd/

-

Tiasha Letostak, PhDhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/tiasha-letostak-phd/July 14, 2014

-

Tiasha Letostak, PhDhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/tiasha-letostak-phd/September 3, 2014