What’s the Relevance of Emotional Intelligence in Medicine?

What’s the Relevance of Emotional Intelligence in Medicine? https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Emotional-Intelligence-Graphic-1024x386.jpg 1024 386 Mike Patrick, MD and Erica Banta, MBA, LDSS Mike Patrick, MD and Erica Banta, MBA, LDSS https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Michael-Patrick.jpg- September 22, 2022

- Mike Patrick, MD and Erica Banta, MBA, LDSS

The practice of clinical medicine requires an intelligent mindset. Strong cognitive intelligence (IQ) is required to develop and maintain a substantial knowledge base and to call upon the critical thinking skills needed to synthesize a hundred points of data into a meaningful clinical picture, correct diagnosis and appropriate management plan. But another type of intelligence is equally important: emotional intelligence (EQ). Emotional intelligence powers our feelings, responses and engagement with colleagues and patients. It is a stronger predictor of success than IQ and (unlike IQ) it can be developed over time.

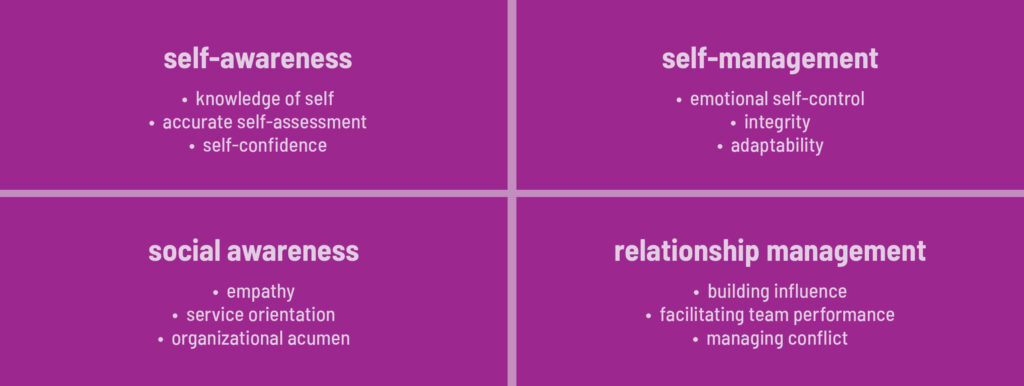

Emotional intelligence is rooted in four quadrants: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness and relationship management.

Personal Competence

The first two quadrants form the basis of one’s personal competence. During the day, feelings — both positive and negative — come in and out of our consciousness. When we experience feelings that are perceived as negative, it is useful to reflect on their source.

Why are we having these feelings? The source may be readily apparent, or it may take some digging to understand their significance. Perhaps we are frustrated with the morning commute or disappointed that our schedule is too full… or too light. We might even be angry because a particular patient has failed to show up for an appointment again or because we have provided the same feedback to an employee over and over without resolution of a particular problem.

By identifying the source of our feelings, we can begin to process them in a healthy way. This, in turn, will boost our professionalism, our mood and the influence we have on those whose paths we cross in the course of our work.

Our feelings influence our behaviors. Upon entering the brain, sensory information passes through the limbic system on its way to the frontal cortex. This pathway attaches emotions to the data. The frontal cortex then processes the sensory and emotional data and sends messages back to the body, which take the form of behavior. This behavior is manifest as spoken words and changes in our non-verbal body language such as posture, gestures, facial expressions and eye contact.

When emotions are left unchecked, the thinking part of the brain is likely to place critical importance on them. This may result in a sharp word or body language that is incongruent with professionalism in clinical and learning environments. This can decrease our effectiveness as we engage with others and negatively impact the morale of our team.

However, if we practice self-awareness and understand where our feelings come from and why we feel them, the frontal cortex can take this additional information into account and respond in a more effective and constructive way. Instead of a sharp word about the patient who chronically misses an appointment, we may come to understand their transportation challenges, which motivates us to connect the family to reliable transportation resources.

Social Competence

The final two quadrants create one’s social competence. Social awareness is the ability to understand the emotions, needs and concerns of other people, pick up on emotional cues, feel comfortable socially and recognize the power dynamics in a group or organization. Social awareness can also encapsulate the skill of treating people according to their emotional reactions, which can also be known as empathy.

Hearing what the other person is “really” saying is a key component of social awareness. When we are active listeners, we stop talking and pause the inner monologue in our own minds. Active listening can prevent a misdiagnosis and help to build relationships with patients, families and even colleagues.

Creating and maintaining good working relationships can heavily impact the patient experience and is rooted in social awareness. These relationships can be, and often are, mirrored by students in a learning environment. Clinicians who are also teachers have a responsibility to demonstrate positive relationships with other doctors, nurses, support staff and others.

Relationship management is the ability to develop and maintain good relationships, communicate clearly, inspire and influence others, work well in a team and manage conflict. It is the culmination of the previous three quadrants in that it takes into consideration awareness of one’s own self and emotions and combines the skill of empathy and listening to manage interactions.

Leadership and influence can be direct effects of positive relationship management. Cooperation, collaboration and better decision-making are unequivocal results of the influence that stems from intentionally practicing relationship management. When teams are operating at their best, with trust and solid relationships at the foundation, those who lead and teach can quickly assess the strengths and opportunities of those around them, and the barriers of finding expedited solutions begin to break down.

In all relationships (personal and professional) conflict and disagreements are inevitable. Two people cannot possibly have the same needs, opinions and expectations at all times. However, resolving conflict in healthy constructive ways can strengthen trust between people. When conflict isn’t perceived as threatening or punishing, it fosters freedom, creativity and safety in relationships.

Once we know how to manage stress, stay emotionally present and aware, communicate nonverbally and actively listen, we will be better equipped to handle emotionally charged situations and conflicts, enabling us to catch and defuse many issues before they escalate.

Emotional Intelligence has been an important topic in the business and organizational leadership spaces for decades.

The propensity to actively use the skills of EQ can be a great predictor of organizational success. It is equally important in health care. Administrators, clinicians, professors and other medical professionals can leverage the tenants of EQ to understand and manage their own stress and emotions, build better relationships, foster higher performing teams and reinforce positive patient outcomes.

The need for EQ is higher today than ever. Self-awareness and relationship building are now the currency of a health care economy that has the human at the center.

Learn More With PediaCast CME Faculty Development

Erica and Mike dig deeper into emotional intelligence in clinical and academic medicine in a recent episode of PediaCast CME. PediaCast CME episodes are also worth 1 credit of CME/CE.

Looking for more? PediaCast CME episode 080 looks at academic bullying in the medical setting with guest Maya Iyer, MD.

About the author

Michael D. Patrick, Jr, MD is a member of the Section of Emergency Medicine, medical director of Digital Health for Nationwide Children's Hospital, and an assistant professor of Clinical Pediatrics at The Ohio State University College of Medicine. His clinical interests include helping sick and injured children in Nationwide Children's off-site urgent care network and the main campus emergency department. He is also interested in parent and patient education. Since 2006, he has hosted and produced PediaCast: a pediatric podcast for parents. This popular program covers news parents can use, answers listener questions, and interviews pediatric and parenting experts. PediaCast is the most-listened-to online source of pediatric information with over four million downloads to date. PediaCast is available wherever podcasts are found.

Erica Banta, MBA, LDSS, is the director of Talent Management at The Ohio State University.

-

Erica Banta, MBA, LDSShttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/erica-banta-mba-ldss/September 22, 2022

- Posted In:

- Features

- Second Opinions