What Can Bench Science Teach Us About Opioid Abuse?

What Can Bench Science Teach Us About Opioid Abuse? https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/themes/corpus/images/empty/thumbnail.jpg 150 150 Abbie Miller Abbie Miller https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/051023BT016-Abbie-Crop.jpg- October 22, 2018

- Abbie Miller

Irina Buhimschi, MD, is an obstetrician and principal investigator best known for her work to prevent prematurity. As director of the Center for Perinatal Research in The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, she says the opioid crisis has caused the center to adjust priorities.

“There are a lot of things that we don’t know about how opiate exposure affects the fetus in utero, and how that exposure will affect the child long term,” she says. “While we’ve made significant progress in the clinical care of these babies in terms of length of stay, we have an opportunity to further improve outcomes through basic research.”

Among the questions that are unanswered:

- Is buprenorphine or methadone a better maintenance medication for pregnant women? Is there a genetic footprint that makes one better than another for a specific individual?

- Which medication – methadone, morphine or buprenorphine – is best for treating NAS?

- Why do some opioid-exposed babies develop NAS while others never withdraw? Is there a genetic susceptibility?

- How does the placenta metabolize illicit drugs, and how do those metabolites affect the fetal brain?

These questions are all difficult to study in the clinic.

“We have a group that has created different models to study some of these questions in vitro. Using these models, we’re able to look at the genomics, proteomics and metabolomics involved,” says Dr. Buhimschi, who is also a professor of Pediatrics and Obstetrics and Gynecology at The Ohio State University.

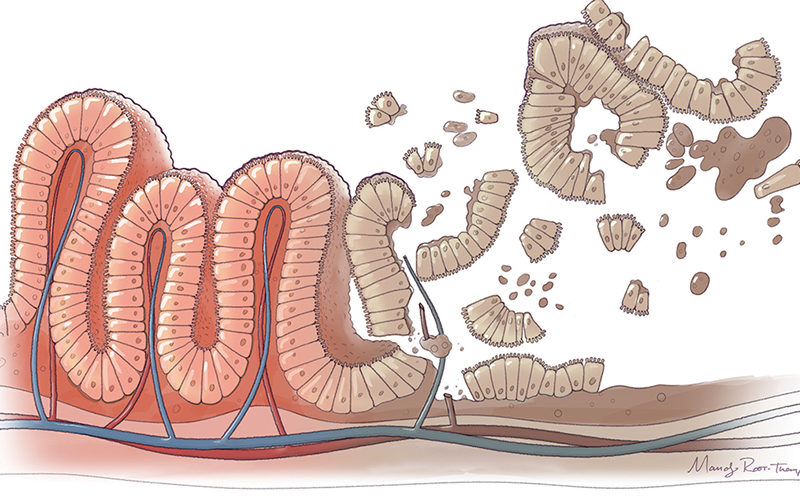

The models in question are organoids developed from induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which are derived from skin or blood cells that have been reprogrammed back into an embryonic-like pluripotent state. Organoid placentas and brains hold incredible potential to answer questions about the role of all these “omics” in fetal drug exposure.

These models will enable the team to conduct several collaborative experiments aimed at better understanding the underlying mechanisms of NAS.

“ONE OF THE MAJOR PROBLEMS IN STUDYING THE IMPACTS OF PRENATAL EXPOSURE IS THAT WE USUALLY DON’T KNOW WHAT EXACTLY THE BABY WAS EXPOSED TO.” – MARK KLEBANOFF, MD

UNDERSTANDING EXPOSURES

“One of the major problems in studying the impact of prenatal exposure to drugs is that we usually don’t know what exactly the baby was exposed to,” says Mark Klebanoff, MD, director of the Ohio Perinatal Research Network. “In previous studies of marijuana use, we found that the accuracy of self-reporting was poor.”

In those studies, mothers’ responses compared to blood and urine toxicology often did not match up. Sometimes, mothers who said they had used marijuana during pregnancy had clean toxicology screens. Many times, mothers who said they did not use marijuana during pregnancy had positive toxicology screens.

When illicit substances are involved, knowing just what the baby was exposed to is even more difficult.

“Being illicit, those drugs could have anything in them,” says Dr. Buhimschi. “We need ways to really understand what the exposures are. When we know that some exposure is present, umbilical cord blood toxicology and a urine screen from the mother can be helpful.”

But it’s nearly impossible to get good toxicology results for every opioid-exposed infant. Without that data, researchers can’t accurately draw correlations between specific exposures and NAS symptoms.

Dr. Buhimschi’s team hopes to be able to provide a controlled way to test different drugs and combinations of drugs on placental organoids. This may shed some light on which factors are the most important for predicting which babies will develop NAS.

“The placenta is likely a key factor in determining which babies develop NAS and which do not,” says Dr. Buhimschi. “We don’t know if the placenta is a high or low metabolizer of opioids. Other researchers do these experiments with viruses, we’re trying to do it with drugs.”

LONG-TERM EFFECTS

Another unknown is the long-term effects of opioid exposure on neurodevelopment. According to Dr. Klebanoff, who is also a principal investigator in the Center for Perinatal Research at Nationwide Children’s and a professor of Pediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Epidemiology at The Ohio State University, what little we know suggests that executive function is impacted later in childhood. But it is difficult to determine whether that is due more to the prenatal opioid exposure or to their environment.

“These mothers and children often end up back in the environment that contributed to the opioid abuse in the first place,” he says. “At this point, we can’t say whether some deficits in executive function at ages 5, 6 or 7 are the result of the prenatal exposure or the result of social determinants. It’s probably some of both.”

Again, Dr. Buhimschi’s team believes that their models can help answer some of the neurodevelopmental questions.

“We’ve developed a brain organoid – in addition to a placental organoid – to create an in vitro model, a co-organoid system, to study the relationship between the placenta and brain,” she says. “We hope to mimic the transmission of metabolites from the placenta to the fetal brain, then use an electroencephalogram (EEG) to measure the changes in electrical signals caused by exposure to those opioid metabolites.”

MOVING FROM POSSIBLE TO PRACTICAL

As the researchers refine and validate the models and methodologies, they are also working to secure grant funding to do the experiments.

“By doing the experiments and collecting the data, we hope to learn valuable information that can be translated into practical solutions to further improve clinical care for these mothers and babies,” says Dr. Buhimschi.

This story also appeared in the Fall/Winter print issue, “The Impact of Opioids on Children.” Download the PDF of the issue.

About the author

Abbie (Roth) Miller, MWC, is a passionate communicator of science. As the manager, medical and science content, at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, she shares stories about innovative research and discovery with audiences ranging from parents to preeminent researchers and leaders. Before coming to Nationwide Children’s, Abbie used her communication skills to engage audiences with a wide variety of science topics. She is a Medical Writer Certified®, credentialed by the American Medical Writers Association.

-

Abbie Millerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/abbie-miller/

-

Abbie Millerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/abbie-miller/

-

Abbie Millerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/abbie-miller/

-

Abbie Millerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/abbie-miller/

- Posted In:

- Features