Discovery to Drug Development: Expanding the Role of Academic Centers

Discovery to Drug Development: Expanding the Role of Academic Centers https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/DSC_1346_Small-header-1024x575.gif 1024 575 Abbie Miller Abbie Miller https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/051023BT016-Abbie-Crop.jpg- April 24, 2017

- Abbie Miller

As more researchers at academic centers become involved in drug development, institutions are responding with support and guidance.

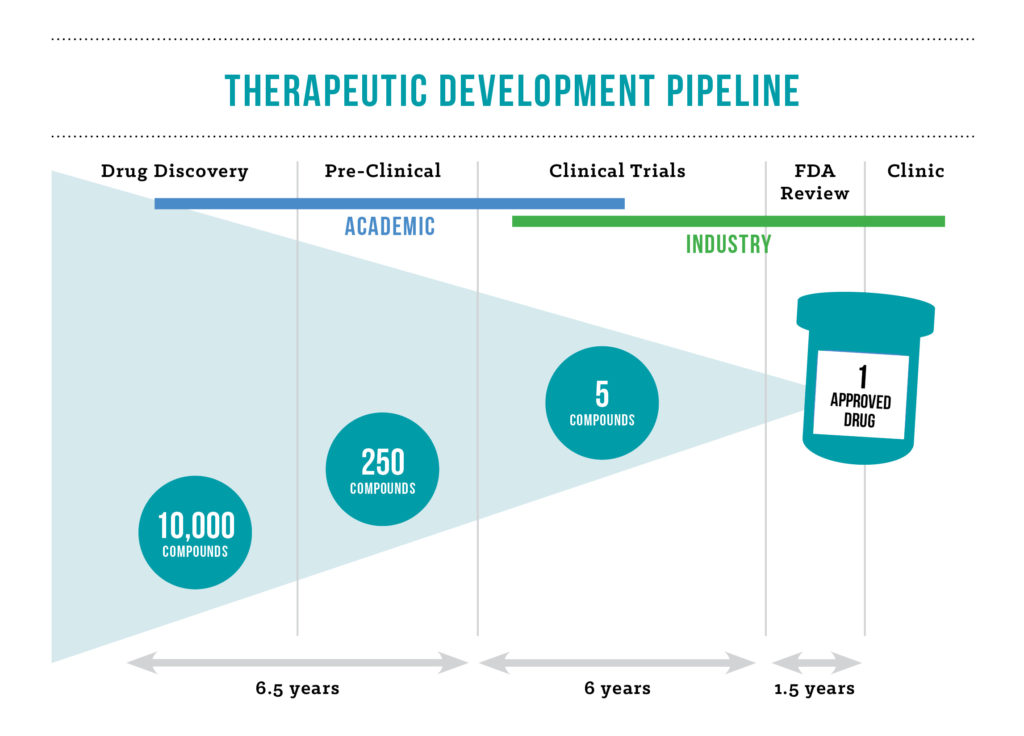

Researchers at academic institutions regularly make discoveries about disease processes and potential therapeutic agents. Translational medicine is focused on moving these discoveries out of the laboratory and into the clinic where they can potentially help patients. But creating a new treatment or medication – drug development – is a completely different process with its own set of challenges as compared to research work common in the academic setting.

Academic research and drug discovery diverge in key ways – from the primary goals and objectives to how they are funded and the institutional support required. And as more researchers embrace the opportunity to pursue drug development at academic centers as a way to move their discoveries from the lab bench to the patient bedside, institutions and the pharmaceutical industry are responding.

“We, at academic centers, have a unique opportunity to develop new drugs and repurpose old drugs for patients desperately in need of them,” says Christopher Shilling, MS, director of Drug and Device Development Services at The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. “Drug discoveries are continuously happening in academic centers. The challenge is moving these discoveries into a drug development process more common in the industry. This is a particularly viable option for patients with rare diseases in which the pharmaceutical industry is not investing.”

Thinking Steps Ahead

Academic centers with the right resources can conduct the right studies to bring down the risk level for industry to invest in drugs at early investigational stages. In order to do so, strategy and intention are needed to bridge the gap from academic research to drug development.

“Most researchers aren’t trained to think about how to approach developing something as a therapy versus doing scientific research on the agent,” says Chad Bennett, PhD, director of medicinal chemistry for the Drug Development Institute (DDI) at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James). “The sooner a researcher begins to think about the criteria and information the FDA and pharmaceutical industry will want, the better off he or she will be to develop the needed experiments.”

Academic centers are increasingly investing in drug development, shifting resources and forming programs through which researchers can get the support they need.

“At the DDI, we seek out and support research technologies developed at OSU and vet them for potential commercial and clinical success,” says Dr. Bennett. “Everyone on our team has a background in pharma, so we can guide and support the researchers through the process.”

Beyond counseling investigators, setting up milestones and adding team members, the DDI provides investment funds to supplement the grants earned by the researchers.

“Our plan is to move the product through development as quickly as possible,” explains Dr. Bennett. “Once we have secured an intellectual property patent, the clock is ticking. Many times research grant money doesn’t support the type of experiments needed to get the drug into a phase 1 clinical trial as quickly as we need it to. So we supplement with investment dollars that are based on achieving milestones in the development pathway.”

In doing so, the DDI team assists investigators in both furthering their academic careers and getting drugs to the marketplace.

At Nationwide Children’s, the Drug and Device Development Services team aims to engage researchers early on in the process.

“We start from the researchers’ vision of what the product would be as a commercial entity,” says Shilling. “Then, we guide the researchers to take the required steps to make their work more acceptable by federal regulators and valued from a commercial viewpoint. We go from an initial research concept to engaging the right people, and then guide them towards the appropriate next steps.”

Researchers at Nationwide Children’s are encouraged to consider what studies would need to be done to get a drug product to market as they are writing their grants, explains Shilling. In this way, grant funding may support some of the activities needed for drug development. Another key area of focus for the program is building relationships with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and educating all faculty about the opportunities to work with the FDA.

In the pharmaceutical industry, checkpoints, reviews and quality checks are designed with the FDA process in mind. Vetting the potential product is done continuously during development, which is a challenge for academic centers. According to Shilling, academic centers have great researchers doing high-quality research, but lack some of the resources for vetting that are common in industry.

“Our approach is to train researchers to be FDA compliant, to be proactive in doing things in ways that will help ensure a smooth process when the time comes to go to the FDA,” says Shilling. “To be most successful, we want them to look years ahead of their initial research question.”

Researchers at Nationwide Children’s are encouraged to consider what studies would need to be done to get a drug product to market as they are writing their grants, explains Shilling. In this way, grant funding may support some of the activities needed for drug development. Another key area of focus for the program is building relationships with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and educating all faculty about the opportunities to work with the FDA.

In the pharmaceutical industry, checkpoints, reviews and quality checks are designed with the FDA process in mind. Vetting the potential product is done continuously during development, which is a challenge for academic centers. According to Shilling, academic centers have great researchers doing high-quality research, but lack some of the resources for vetting that are common in industry.

“Our approach is to train researchers to be FDA compliant, to be proactive in doing things in ways that will help ensure a smooth process when the time comes to go to the FDA,” says Shilling. “To be most successful, we want them to look years ahead of their initial research question.”

Moving into the Marketplace

Both Shilling and Dr. Bennett note that academic centers can only take drug development so far and that partnering with pharmaceutical companies, either big pharma or smaller start-ups, is essential to getting the product to market.

“At an academic center, we can’t bring the drugs and devices that we develop all the way to market. We need to create partnerships. This involves engaging with technology commercialization resources at the academic centers to help find and curate industry partnerships,” says Shilling.

Part of that enticement for industry partners is to show a lower investment risk to increased value proposition.

“By vetting the drugs and getting them into early stage clinical trials, we are able to show preliminary safety and efficacy, making them more appealing to companies looking to invest,” says Shilling. “If we can decrease the risk associated with an investigational drug, we’ll be more successful in finding a partner to bring it to market,” says Dr. Bennett. “The competitive landscape, however, plays a significant role in when the partnerships are likely to happen.”

For drugs developed for very small patient populations, large pharmaceutical companies may never be the ideal partner. An increasing number of start-ups, often formed by angel investors or funded by patient foundations or advocacy groups, may be more willing to take on the risk of a developmental drug for a small patient population. Bigger companies are in the space, but they tend to wait – it is uncommon for them to invest where high risk is maintained, according to Shilling. These higher risk, smaller patient population scenariosare also new ground for the FDA.

“One question the FDA has yet to answer is how to regulate personalized medicine,” says Shilling. “In most cases, even with a small patient population, a potential therapeutic must still follow the traditional FDA process. But in cases where your drug intends to only treat a single individual, there’s no clear process for that.”

“We are in the unique position to be at the table for early conversations about how to manage and regulate these personalized medicine products, both within our institution and nationally,” he elaborates. “We’ve had early conversations about personalized medicine drug development and are hopeful to see these conversations continue with the FDA.”

Regardless of the size of the prospective patient population, Shilling and Bennett agree that it’s never too early to consider what the research should look like as a product. That vision, combined with the right tools and resources will help make the process more efficient.

“Having the right people on your team can be the difference between just having a good idea and launching a successful product,” says Shilling. “It’s never too soon to reach out.”

Image credits: Nationwide Children’s

About the author

Abbie (Roth) Miller, MWC, is a passionate communicator of science. As the manager, medical and science content, at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, she shares stories about innovative research and discovery with audiences ranging from parents to preeminent researchers and leaders. Before coming to Nationwide Children’s, Abbie used her communication skills to engage audiences with a wide variety of science topics. She is a Medical Writer Certified®, credentialed by the American Medical Writers Association.

-

Abbie Millerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/abbie-miller/

-

Abbie Millerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/abbie-miller/

-

Abbie Millerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/abbie-miller/

-

Abbie Millerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/abbie-miller/

- Posted In:

- Features