Bias: Do You See What Influences You?

Bias: Do You See What Influences You? https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Winter-2019_Color-Cover-header-web-1024x575.jpg 1024 575 Abbie Miller Abbie Miller https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/051023BT016-Abbie-Crop.jpg- October 10, 2019

- Abbie Miller

In the United States, children of color have worse clinical outcomes than white children. Racial disparities have been documented in nearly every pediatric specialty. Among the most studied and most widely perpetuated disparities are those between black and white children.

For example:

- The infant mortality rate, while declining overall, is nearly three times higher for black babies than for white babies.

- Black children are less likely to get adequate pain control compared to white children.

- Providers often assume black children are older than they are.

- Black school-age youth are more likely to die by suicide than white youth, though the trend is reversed for teens.

- Black children with moderate to severe congenital heart disease (CHD) are less likely to continue follow-up care with a CHD specialist compared to white counterparts.

- For children with Down syndrome, the life expectancy for white patients is nearly double that of black patients.

These differences are not the result of any inherent biological differentiator. The studies’ analyses show they are not purely driven by differences in socioeconomic backgrounds, such as education, income and zip code. They are at least in part the result of race, or more specifically the socioeconomic, psychological, and physiologic outcomes of toxic race relations.

The idea of race is not clinical or biological in nature. It’s a social construct that, in the United States, was institutionalized in the late 1600s to make legal distinctions between “white” and “black” residents. And it’s a social construct still at work today. In most studies that look at disparities in care and outcomes based on race, the term is meant to identify a cultural group defined by ethnic heritage, skin color and personal identity.

“Race and racism in America is an issue in every part of life. And for children, our most vulnerable population, it affects health outcomes even before they leave the womb,” says Adiaha Spinks-Franklin, MD, MPH, attending physician in Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics at Texas Children’s Hospital. “Only by talking about these issues openly, relying on facts and evidence, and confronting bias head on will we make progress toward health equity for children everywhere.”

“Race and racism in America is an issue in every part of life. And for children, our most vulnerable population, it affects health outcomes even before they leave the womb. Only by talking about these issues openly, relying on facts and evidence, and confronting bias head on will we make progress toward health equity for children everywhere.”

– Adiaha Spinks-Franklin, MD, MPH, attending physician in Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics at Texas Children’s Hospital

Beyond Social Determinant to Adverse Childhood Experience

In July 2019, the American Academy of Pediatrics released a policy statement calling for pediatricians to confront the impacts of racism on children. According to the policy statement, racism – the implicit prejudicial treatment of someone based on race – has a “profound impact” on the health status of youth and their families. The statement goes on to add, “Although progress has been made toward racial equality and equity, the evidence to support the continued negative impact of racism on health and well-being through implicit and explicit biases, institutional structures, and interpersonal relationships is clear. Failure to address racism will continue to undermine health equity for all children, adolescents, emerging adults, and their families.”

The experience of racism and racial bias should be considered an adverse childhood experience (ACE), like abuse, neglect or traumatic events that predispose a child to a negative outcome later in life. Dr. Spinks-Franklin, who is also an associate professor of Pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine, and Jennifer Walton, MD, MPH, attending physician in Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics at Nationwide Children’s, and their colleagues spend the first part of their wildly popular workshop “Racism: Another Adverse Childhood Experience,” laying out the evidence for why this is true. The workshop was developed for and by the Society of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics in 2018. It was presented to a standing-room-only crowd at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting in April of 2019, and it has been shared around the country since then.

“The lived experience of racism – witnessing its impacts, experiencing it firsthand – has serious consequences to the emotional, physical and mental well-being of children, in addition to the known disparities in care that can arise as a result of provider bias,” says Dr. Walton, who is also an assistant professor of Clinical Pediatrics at The Ohio State University.

“The lived experience of racism – witnessing its impacts, experiencing it firsthand – has serious consequences to the emotional, physical and mental well-being of children, in addition to the known disparities in care that can arise as a result of provider bias.”

– Jennifer Walton, MD, MPH, attending physician in Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics at Nationwide Children’s

Implicit or Explicit? Understanding Bias

The way one person interacts with another is influenced by a myriad of factors, guided by complicated algorithms our brains have developed over our evolutionary and personal histories.

“We all make assumptions and categorize people in every way – gender, race, age – and all those assumptions are often useful and helpful in getting us through the day. We don’t have time to think through every encounter, so we use categories as shortcuts,” says Deena Chisolm, PhD, director of the Center for Innovation in Pediatric Practice and director of the Center for Population and Health Equity Research at the Abigail Wexner Research Institute (AWRI) at Nationwide Children’s.

Those quick assessments can become the basis for stereotypes and biases. Implicit bias refers to the unconscious attitudes and stereotypes that affect our understanding, feelings and actions – whether in a positive or negative way.

“Unchecked, bias erodes quality of care and eats away at our ability to provide care at the therapeutic level,” says Kelly Kelleher, MD, MPH, vice president of Community Health and principal investigator in the Center for Innovation in Pediatric Practice in the AWRI at Nationwide Children’s.

Bias is looking at a family and first asking for a Medicaid card instead of a card for private insurance. It is asking certain patients about drug use and not others. It is assuming an injury was caused by abuse in one patient and happened during a sporting event for another. In short, bias is allowing assumptions to override evidence.

“These small slights are sometimes referred to as micro-aggressions. When they happen to a patient, it builds scars and callouses and negative feelings,” says Dr. Chisolm, who is also vice president for Health Services Research in the AWRI. “Once or twice it’s irrelevant, but when it’s daily, weekly and monthly for a lifetime, it creates barriers to interacting. And it can create mistrust of the health care system and the people in it.”

“We all make assumptions and categorize people in every way – gender, race, age – and all those assumptions are often useful and helpful in getting us through the day. We don’t have time to think through every encounter, so we use categories as shortcuts.”

– Deena Chisolm, PhD, director of the Center for Innovation in Pediatric Practice and director of the Center for Population and Health Equity Research at the Abigail Wexner Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s

When Bias is Exacerbated

“Bias becomes more profound, more exacerbated, when providers are tired, stressed or overwhelmed,” says Dr. Kelleher, who is also a distinguished professor of Pediatrics and Public Health at The Ohio State University. “The more cognitive demand we have, the more biased we are.”

A series of studies led by Tiffani Johnson, MD, MSC, attending physician in Emergency Medicine at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, investigated the role of implicit bias in the pediatric emergency department. In 2013, she published an article in Academic Emergency Medicine that showed how stress and fatigue influence bias. The study found that increased stress was associated with greater implicit racial bias.

In 2016, Dr. Johnson published a follow up in Academic Pediatrics investigating if ED physicians were less biased against children compared to adults and if the age, race, gender or level of training of the provider mattered. She and her colleagues found that most residents had pro-white/anti-black bias on both the child and adult implicit bias tests used. They also showed that the residents’ biases did not vary based on personal characteristics and mirrored the biases shown in other specialties.

Even more recently, a study published in JAMA Network Open in 2019 showed that as burnout symptoms increased so did racial bias. The study followed non-black medical residents who self-reported symptoms of burnout during their second and third years of residency. The medical residents completed tests aimed to identify explicit and implicit biases.

“With increasing rates of burnout and a growing focus on the mental and emotional health of health care providers, we should be considering how functioning in this state affects the bias experienced by patients of color,” says Dr. Walton, who is also chair of the Pediatric Section of the National Medical Association.

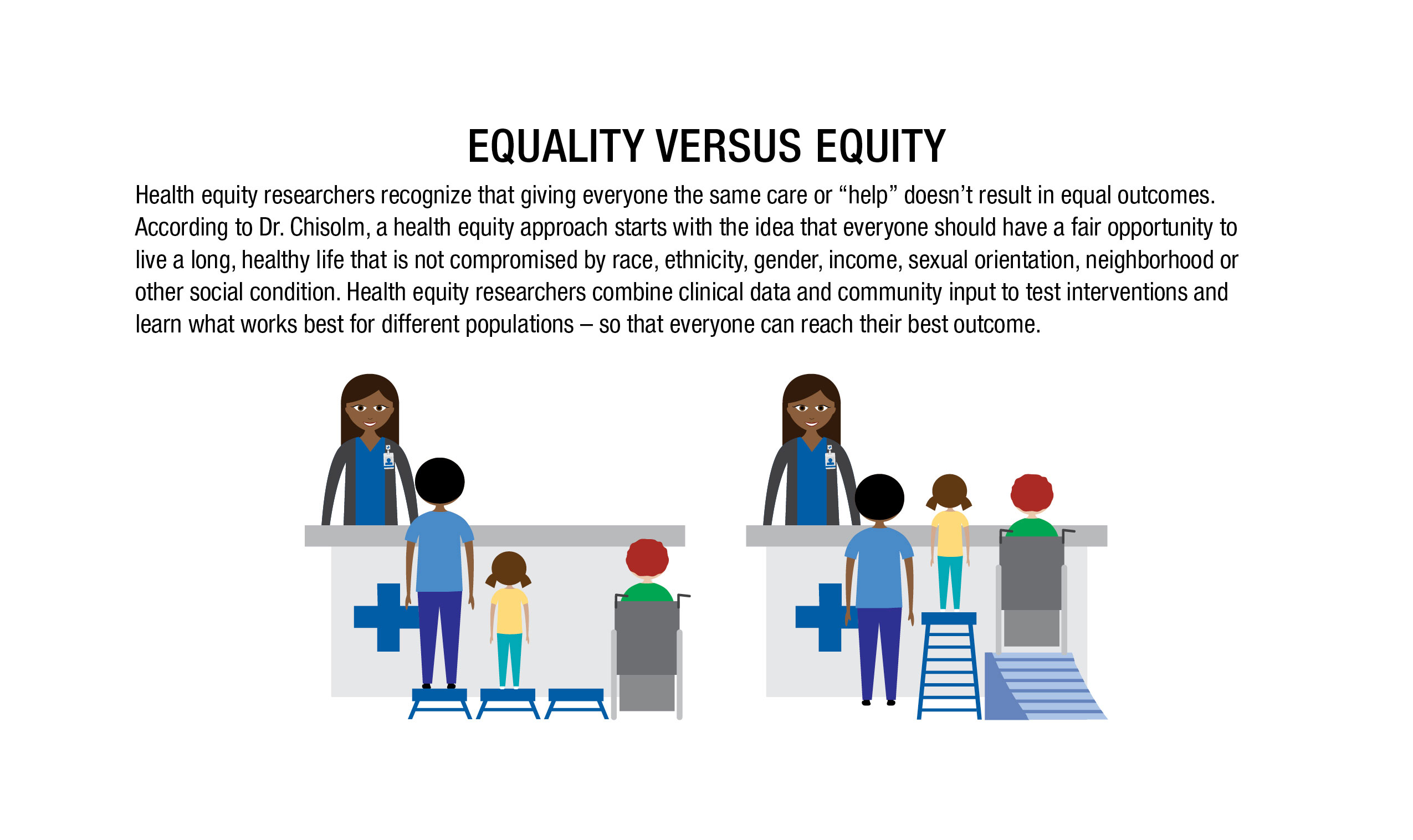

Equality Is Not Equity

At a system level, algorithm-based care, protocols and standardization of care help reduce variation in care that could be caused by bias. This is particularly helpful in reducing variation due to implicit bias when a provider is tired or stressed. But experts warn that all care being equal does not necessarily achieve equity.

“If you look at disparities in life expectancy and infant mortality rates, those won’t be overcome with giving everyone the same care,” says Dr. Chisolm, who is also a professor of Pediatrics at The Ohio State University. “Infant mortality has declined equally for everyone – but that still means there’s a three-fold difference between black and white outcomes.”

The first step to achieving health equity is to provide excellent care for populations who don’t always get it. And one of the hurdles to that care is the perception that some providers look down on some people.

“Patient perspective is critical to providing high quality care. Culture differences, the general stress of interacting with the health care system and bias experienced by patients are all reasons that patients might not feel like they are getting good care,” says Dr. Kelleher, who is also the ADS/Chlapaty Endowed Chair of Innovation in Pediatric Practice in the AWRI.

He shares a story about a public pediatric psychiatry clinic where patients reported that they were getting terrible care. All of the families assumed that they were being disrespected because they were poor or black.

“It matters a lot if you think the system doesn’t care for you or respect you,” Dr. Kelleher says. “We have to address that perception as well as providing consistent, quality care.”

People of color may choose to go to lower quality providers to avoid feeling judgment or disrespect, says Dr. Chisolm. They may avoid a more highly rated facility in favor of another provider because the other provider has more people who look like them and because they feel more welcome. A lot of the disparities in health care outcomes can be traced to the places that people choose to get care, she adds.

Part of the solution, Dr. Chisolm says, lies in making the highest quality institutions places where all people want to go to get care. Not just because families want to receive the best, but because they feel welcome and safe there.

To do so, hospitals and institutions must become explicitly welcoming to all communities. In some instances, this means holding focus groups and developing relationships with community organizations that can help navigate cultural differences. And most importantly, it means listening to and incorporating the feedback, says Dr. Kelleher.

Some of that feedback might require hospitals to become more open to new models of care, which could improve outcomes and lead to more health equity for certain patient groups. Would home visits or telemedicine options help to address the needs of a diverse population? Would they help to build trust between the community and the health care institutions? These are big questions that experts are looking to answer, but they aren’t the only ways to address bias and inequity in health care.

“Ultimately, we won’t get to health equity by just fixing disparities at the health care system level. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t fix it there,” says Dr. Chisolm. “The biggest hurdle to eliminating health disparities has little to do with the provider. It’s getting to the underlying social problems so that more people, particularly those of color, can have a lived experience where they don’t feel like they are constantly under attack – from bill collectors, from schools, from society and so on. Constant stress has biological outcomes.”

Bridging Social Distance

To get beyond the health care system level, Dr. Kelleher suggests providers and health care employees consider interpersonal interactions with patients. The social distance between the patient and the provider is an important component in how bias manifests, says Dr. Kelleher. “The more distant we are, the less likely I am to understand your culture and needs. The less likely I am to control your pain adequately, the more likely I am to prescribe one thing and not another. This social distance and the resulting impacts on care result in lower quality care.”

One way to address the challenges of social distance is to “change who we are,” suggests Dr. Kelleher.

“When our faculty and staff reflect the community around us, when we interact daily with the community outside of the hospital walls through mentoring, festivals and other events, it’s no longer them versus us. It’s just us,” says Dr. Kelleher. “That alone takes away so many of the feelings of fear, anxiety and uncertainty that surround issues of race, racism and implicit bias.”

Reflecting the community also comes down to hiring practices. At Nationwide Children’s, a concerted effort to hire members of the community in the zip codes surrounding the hospital campus has had good success. According to Dr. Kelleher, the next focus is retention.

“We’ve gotten really good at being ‘corporate.’ We need to make sure that we don’t stop being good at being part of the community,” says Dr. Kelleher. “The whole idea of becoming ‘us’ points to becoming a front porch for the community. Until we are able to achieve that, we’ll continue to struggle with social distance and implicit bias.”

“When our faculty and staff reflect the community around us, when we interact daily with the community outside of the hospital walls through mentoring, festivals and other events, it’s no longer them versus us. It’s just us. That alone takes away so many of the feelings of fear, anxiety and uncertainty that surround issues of race, racism and implicit bias.”

– Kelly Kelleher, MD, MPH, vice president of Community Health and principal investigator in the Center for Innovation in Pediatric Practice in the Abigail Wexner Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s

Challenge Yourself

Looking at changes that can be implemented at the health care system level and the provider level are the first steps to changing outcomes. But what will it take for significant, lasting change to occur?

“For a provider, where you start is recognizing your bias. Acknowledging that you have a first impression of a person or situation, but then being willing to set that impression aside and look at the specific evidence in front of you,” says Dr. Chisolm. “It might turn out that you were exactly right on your first impression, but maybe more often you might be surprised and find out that you were totally wrong.”

So, how do you identify your biases?

Implicit bias awareness tests, including the Harvard Implicit Association Test, are designed to help individuals understand personal biases.

“Using these tests is often helpful, whether people think they have bias or not,” says Dr. Walton. “Because we all have biases – it’s important to identify them.”

In their workshop, Drs. Spinks-Franklin and Walton and their colleagues lead participants through role playing exercises.

“These role playing activities are an essential part of putting what you learn into action,” says Dr. Spinks-Franklin. “Sometimes people are uncomfortable in these scenarios, doing it in a safe setting like the workshop can help them feel more comfortable when they have to deal with bias and racism in the clinic.”

Being uncomfortable, asking questions, being open to being wrong, these are all the themes that were repeated by the experts. They are the truths that are necessary to move from where we are to where we need to be.

“We invite the audience to get comfortable being uncomfortable,” Dr. Spinks-Franklin adds. “That’s how you become an active anti-racist.”

Unsure about where to start?

Check out these tips from the experts interviewed for this article.

If you are not sure, ask.

- For example, ask families how they prefer that you speak to their children.

- It’s always better to ask than assume.

Attend a class or workshop.

- Many are now available at professional conferences.

- Invite one to come to your institution.

Get involved in diverse communities.

- Closing social distance is good for everyone.

Take time to reflect on your personal biases and commit to changing your actions.

- Take care of yourself so that you can have the emotional and cognitive energy to do the work.

Speak up for others.

- Be an advocate.

- If you see something, say something.

References:

- Dixon G, Kind T, Wright J, Stewart N, Sims A, Barber A. Factors that influence the choice of academic pediatrics by underrepresented minorities. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug;144(2):e20182759.

- Dyrbye L, Herrin J, West CP, Wittlin NM, Dovidio JF, Hardeman R, Burke SE, Phelan S, Onyeador IN, Cunningham B, van Ryn M. Association of racial bias with burnout among resident physicians. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(7):e197457.

- Haisnain-Wynia R, Baker DW, Nerenz D, Feinglass J, Beal AC, Landrum MB, Behal R, Weissman JS. Disparities in health care are driven by where minority patients seek care. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:1233-1239.

- Johnson TJ, Hickey RW, Switzer GE, Miller E, Winger DG, Nguyen M, Saladino RA, Hausmann LR. The impact of cognitive stressors in the emergency department on physician implicit racial bias. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2013;23(3):297-305.

- Johnson TJ, Winger DG, Hickey RW, Switzer GE, Miller E, Nguyen MB, Saladino RA, Hausmann LR. Comparison of physician implicit racial bias toward adults versus children. Academic Pediatrics. 2017;17(2):120-126.

Image credits: Nationwide Children’s

About the author

Abbie (Roth) Miller, MWC, is a passionate communicator of science. As the manager, medical and science content, at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, she shares stories about innovative research and discovery with audiences ranging from parents to preeminent researchers and leaders. Before coming to Nationwide Children’s, Abbie used her communication skills to engage audiences with a wide variety of science topics. She is a Medical Writer Certified®, credentialed by the American Medical Writers Association.

-

Abbie Millerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/abbie-miller/

-

Abbie Millerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/abbie-miller/

-

Abbie Millerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/abbie-miller/

-

Abbie Millerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/abbie-miller/

- Posted In:

- Features