Cylinder Mitral Valve Construct is a Safe and Durable Alternative for Young Patients

Cylinder Mitral Valve Construct is a Safe and Durable Alternative for Young Patients https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/4dc2b000-8f21-11e7-aa62-e89a8fb23f02-1024x752.jpg 1024 752 Mary Bates, PhD Mary Bates, PhD https://secure.gravatar.com/avatar/c6233ca2b7754ab7c4c820e14eb518c8?s=96&d=mm&r=g- August 04, 2021

- Mary Bates, PhD

The new technique could potentially reduce the number of lifetime surgeries required by these patients, researchers say.

In a new study, researchers from Nationwide Children’s Hospital report that pediatric patients who underwent cylinder mitral valve construct, a new technique for replacing the mitral valve, had improved left ventricular function over time. In addition, there were no significant differences in echocardiographic parameters between patients who underwent the new technique and those who had more traditional mitral valve replacement procedures.

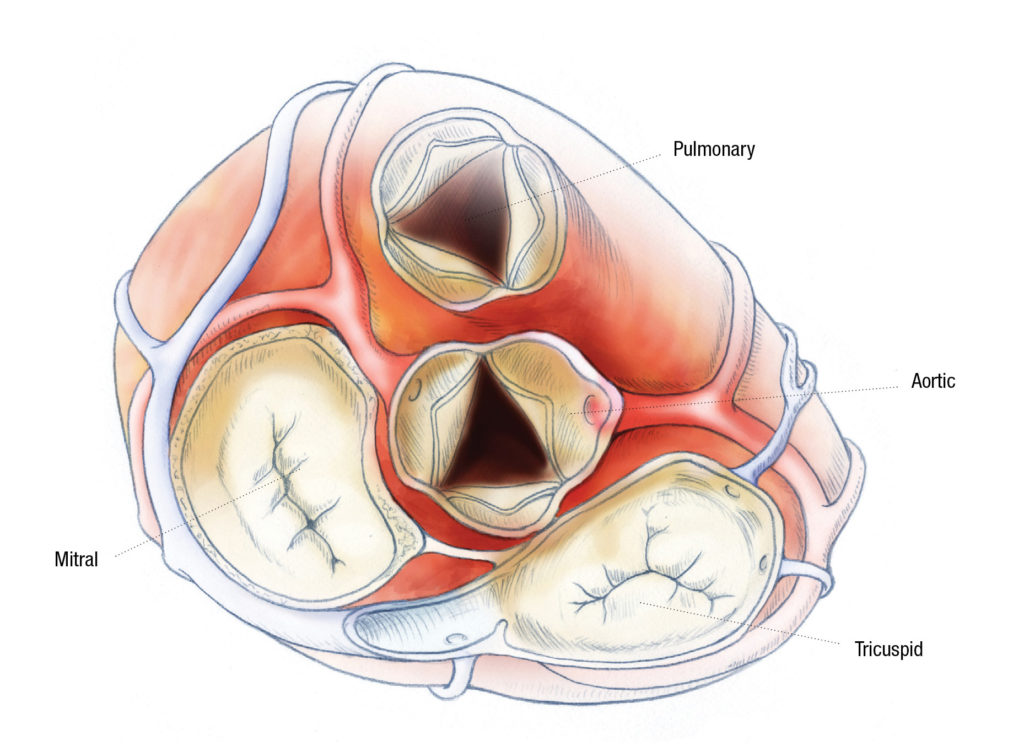

Longitudinal echocardiographic data exist for current mitral valve replacement procedures, including mechanical valves, bioprosthetic valves, and stented bovine jugular valves. However, the cylinder mitral valve construct (cMVC) is a relatively new option for mitral valve replacement in the pediatric population and limited data are available on its practical and theoretical benefits.

“In the last couple years, we’ve used the cylinder valve more frequently than the mechanical valve, particularly in children under the age of one,” says Patrick McConnell, MD, surgical director of the Heart Transplantation and Mechanical Cardiopulmonary Support Programs at The Heart Center at Nationwide Children’s and one of the study’s authors.

“Theoretically, it is more like a normal valve and could potentially have some benefit to a young, growing heart. That is, it is the only type of valve replacement that attaches to all the usual heart structures as a native valve. In particular, the heart muscle so that the muscle continues to receive normal stimulus as it grows compared to the other valve constructs where it is detached.”

Dr. McConnell and colleagues described echocardiographic changes over time in patients that underwent a cMVC and compared echocardiographic changes in those patients to a group of patients that underwent a more traditional mitral valve replacement. They found that the majority of echocardiographic parameters improved over time in cMVC patients, and there were no significant differences between cMVC and other mitral valve replacement patients in echocardiographic values.

“cMVC is a safe alternative that might, in select cases, be a better alternative than a mechanical valve,” says Dr. McConnell, who is also an assistant professor of surgery at The Ohio State University College of Medicine. “Its durability is at least equal to that of a mechanical valve, and a practical benefit is no need for long-term anticoagulation.”

The researchers say that studies with more patients and longer follow-up are needed, but they are hopeful that cMVC has the potential to reduce the number of interventions young patients will need over their lifetimes.

“If you are a one-year-old that requires a mitral valve replacement, you will typically have five or six operations in your lifetime,” says Dr. McConnell. “That’s a heavy burden. If the use of new types of valve constructs can cut that down to even three or four interventions, that’s not perfect, but it’s better.

“We are learning that cMVC is safe, it’s certainly as durable as a mechanical valve, and there are subtle features of the valve that, in a growing young heart, may potentially decrease the number of interventions needed down the road.”

Reference:

Cua CL, Low S, Sisco K, Nicholson L, McConnell PI. Echocardiographic changes in patients with a cylinder mitral valve replacement: Preliminary analysis. Echocardiography. 2021 Jun 29. doi: 10.1111/echo.15132. Epub ahead of print.

Image credit: Nationwide Children’s

About the author

Mary a freelance science writer and blogger based in Boston. Her favorite topics include biology, psychology, neuroscience, ecology, and animal behavior. She has a BA in Biology-Psychology with a minor in English from Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, NY, and a PhD from Brown University, where she researched bat echolocation and bullfrog chorusing.

-

Mary Bates, PhDhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/mary-bates-phd/December 27, 2016

-

Mary Bates, PhDhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/mary-bates-phd/

-

Mary Bates, PhDhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/mary-bates-phd/

-

Mary Bates, PhDhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/mary-bates-phd/

- Posted In:

- Clinical Updates

- In Brief

- Research

- Uncategorized