Beyond A Bigger Workforce: Addressing the Shortage of Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists

Beyond A Bigger Workforce: Addressing the Shortage of Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/071917ds0029-axelson-header-1024x575.jpg 1024 575 David Axelson, MD David Axelson, MD https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/071917ds0029-axelson-crop.jpg- April 10, 2020

- David Axelson, MD

How can the psychiatrists we have make the greatest impact for the most children?

The United States does not have enough child and adolescent psychiatrists. Nearly anyone who works in the field knows about the months-long wait times for new appointments that families can face, or the great distances that some must travel for those appointments.

What we have not really known, however, is the true scope and shape of the problem. A 2018 report from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration called “Behavioral Health Workforce Projections, 2016- 2030” used a mathematical model to find that there was only a 20% greater demand for pediatric psychiatry services than the current supply – and that in a decade, supply would be greater than demand.

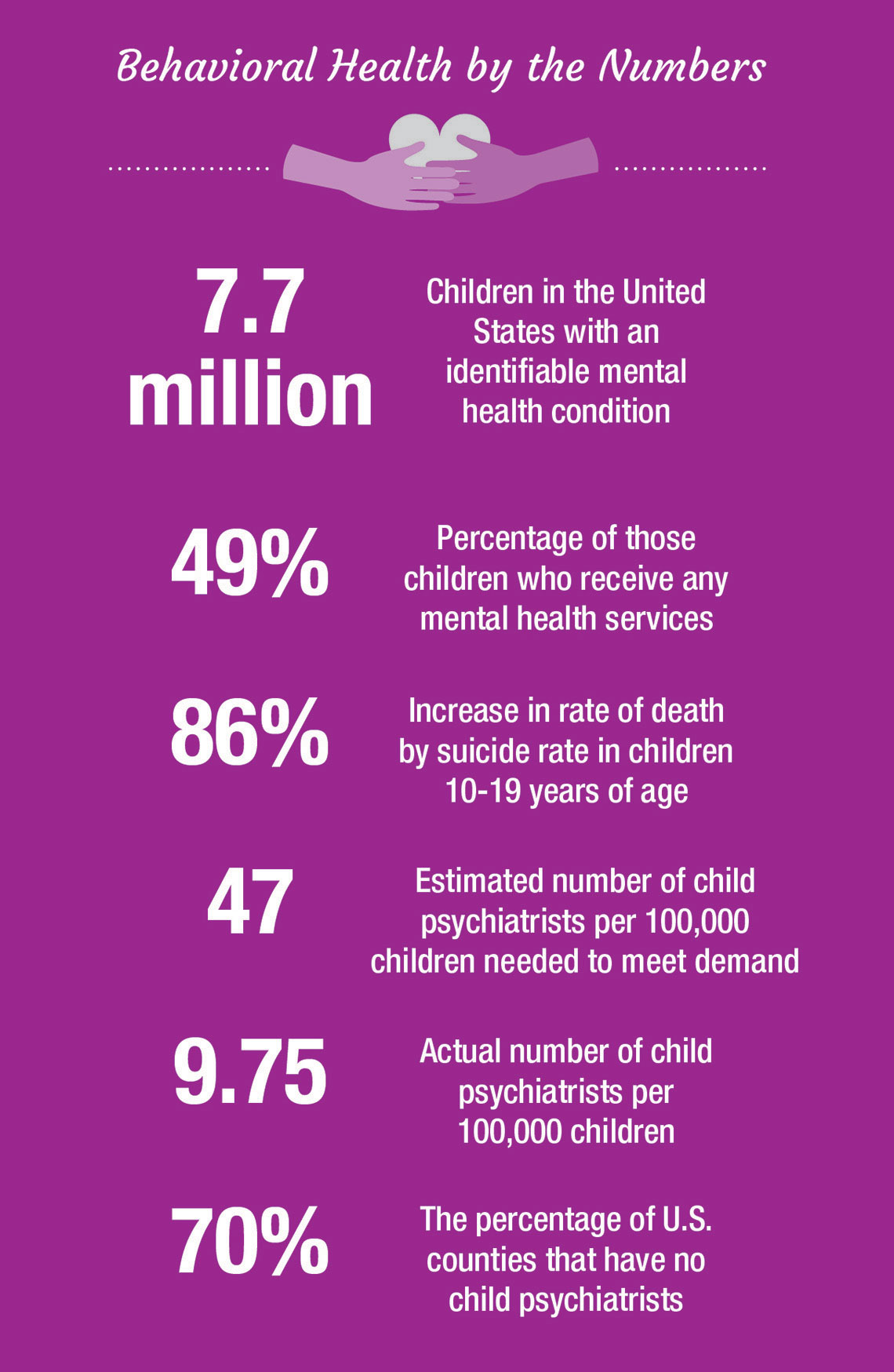

Nothing in my own experience substantiates this, and the significant evidence of a growing mental illness burden among young people may actually refute it. The rate of death by suicide in young people 10-19 years of age increased 86% from 2007 to 2017. Less than half of the 7.7 million children in the United States with an identifiable mental health condition are receiving services from any mental health provider, much less a psychiatrist.

A recent study in Pediatrics from researchers at the RAND Corporation, the University of Georgia and Harvard University gives us a better idea of where we truly stand. Some of what they found is good news. The overall number of child psychiatrists increased 21% from 2007 to 2016, and there are now 9.75 per 100,000 children aged 0 to 19.

But in a broader context, it’s clear that the field isn’t close to having enough child psychiatrists to meet demand, now or in the future. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry estimates that the country needs 47 child psychiatrists per 100,000. That’s four times the number found by the study published in Pediatrics. The ones we do have are heavily concentrated in metropolitan areas; 70% of American counties do not have a child psychiatrist. Massachusetts has eight times the number of child psychiatrists per 100,000 children as Iowa.

So what can be done in the face of these statistics? Many people in the field have proposed ways of increasing the numbers of child psychiatrists, including federal initiatives that would repay school loans, or offering a four-year residency program as an alternative to the typical five-year postgraduate training, or changing codes and reimbursements to better line up with the additional complexity of working with a pediatric population.

Those all have merit, and growing the workforce matters. But it probably isn’t enough, especially when considering the geographical imbalance of that workforce. We should also be asking a question that is informed by a population health approach and considers the limited assets we have now instead of what we may have in the future: how can child psychiatrists have the greatest impact on the most children?

I am the chief of psychiatry and behavioral health at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, and we have wrestled with this very question as we open a new center for research and treatment, the Big Lots Behavioral Health Pavilion. We have come to the realization that a better, more integrated system of care throughout our region can multiply the impact of the child psychiatrist.

In this concept, the psychiatrist leads a multidisciplinary team that could include advanced practice providers, psychologists, nurses, therapists and a variety of other mental health professionals. The psychiatrist treats the group of patients who need psychiatric expertise, while acting as a consultant or advisor to other team members. The psychiatrist may also work with primary care providers, school-based health care professionals and others to expand care to underserved areas. Telehealth technology can improve the quality and efficiency of this care expansion.

This model means psychiatrists, and pediatric psychiatric training, must evolve. Psychiatrists will still work with individual patients, but it’s not all they will do. They must be prepared to build and lead teams and to effectively communicate with a range of health care professionals inside their home institutions and out in their communities.

It will take time and investment, but I believe that both integrated systems of care and efforts to build the workforce are the best strategy for better outcomes. We must be open to these innovative ways of thinking to improve children’s mental health.

This story appeared in the Spring/Summer 2020 print issue. Download the full issue.

References:

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Behavioral health workforce projections, 2016- 2030: psychiatrists (adult), child and adolescent psychiatrists. Bureau of Health Workforce website. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/projections/psychiatrists-2018.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed February 3, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fatal Injury Data: Reports, Charts and Maps. Injury Prevention & Control website. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/fatal.html. Accessed February 3, 2020.

- Whitney DG, Peterson MD. U.S national and state-level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019;173(4):389–391.

- McBain RK, Kofner A, Stein BD, Cantor JH, Vogt WB, Yu H. Growth and distribution of child psychiatrists in the United States: 2007-2016. Pediatrics. 2019 Dec;144(6).

Image credits: Nationwide Children’s

About the author

David A. Axelson, MD, is chief of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health at Nationwide Children's Hospital, chief of the Section of Psychiatry at Nationwide Children's Hospital and the John W. Wolfe Endowed Chair in Pediatric Psychiatry. He is a professor of psychiatry at The Ohio State University School of Medicine and chief of the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center.

- Posted In:

- Features

- Second Opinions