Featured Researcher — Tracy Bedrosian, PhD

Featured Researcher — Tracy Bedrosian, PhD https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/themes/corpus/images/empty/thumbnail.jpg 150 150 Katie Brind'Amour, PhD, MS, CHES Katie Brind'Amour, PhD, MS, CHES https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Katie-B-portrait.gif- March 09, 2022

- Katie Brind'Amour, PhD, MS, CHES

Tracy Bedrosian, PhD, is a principal investigator in the Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine and a specialist in brain mosaicism and neurodevelopment working to uncover the impact that localized mutations in brain cells have on epilepsy symptoms, autism and other neurodevelopmental diseases.

She collaborates with neurologists and other experts in the Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine to sequence brain cell samples from children undergoing surgery for medically intractable epilepsy. Recent research by Dr. Bedrosian and her colleagues, published in Brain, examined variants of the PTEN gene (a regulator of cell growth and survival) found in a single patient with intractable epilepsy and a brain overgrowth syndrome called hemimegalencephaly.

The team confirmed the role of PTEN in hemimegalencephaly by connecting it to regions of the brain where disease was present. She also created the first mouse model to study SLC35A2, a gene implicated in severe epilepsy.

As she and her lab study the location, nature and impact of various mutations on brain development and function, Dr. Bedrosian hopes to uncover information that can one day lead to mutation-specific, targeted therapies for children with challenging neurodevelopmental medical conditions.

Read on to learn more about Dr. Bedrosian and her work.

How did you decide to pursue a career in your field?

I’ve been fascinated by the brain since my first biology class as a teenager. It was mind-boggling to think a bunch of cells make us into the unique, dynamic, imaginative individuals that we are. It’s still difficult to fathom.

As an undergraduate, I started working in the lab of Huda Akil, PhD, a professor at the Molecular Neuroscience Institute at the University of Michigan. I joined partly because of my interest in the brain but mostly because I thought it would check a box for my medical school application. I didn’t know research was a career option.

But I loved every minute of the experience, in no small part due to my outstanding mentors. I spent every possible opportunity outside of class in the lab, which led me to change course and pursue brain research as a career.

What was your path to your current role?

My undergraduate research had focused on genetic and environmental contributors to neuropsychiatric disease, and I was interested in continuing in this line of work. When Randy Nelson, PhD, was at The Ohio State University — he’s now chair of the Department of Neuroscience at West Virginia University — I was drawn to working in his lab for my graduate studies because of his exceptional reputation, both as a scientist and as a mentor.

My thesis project explored how environmental factors can disrupt the circadian system — the body’s clock — and how that disruption influences brain function and susceptibility to depression over the long term. I gained a strong scientific foundation in Dr. Nelson’s lab, as well as some lifelong friends.

As I wrapped up my thesis, I knew that I wanted to learn more about genetics — especially “brain mosaicism,” the idea that different cells within a single person’s brain can have distinct genetic codes. Some people that may be part of what makes us unique, which was something that drove my initial fascination with the brain as a teenager.

I sold most of my belongings, packed up my car and headed west to the Salk Institute in San Diego to join the lab of “Rusty” Gage, PhD, who was on the forefront of studying how brain mosaicism arises. During my time as a postdoctoral fellow in his lab, I got a crash course in genetics and dove into the field of brain mosaicism.

I also became intrigued by the dynamic biotechnology scene in San Diego and the idea of translational research. I eventually left Dr. Gage’s lab and joined a venture development firm, Neurotechnology Innovations Translator (NIT).

Fun Facts About Dr. Bedrosian

What do you usually eat for breakfast?

A bagel or oatmeal … and always coffee. Coffee is very important.

What’s your favorite food?

Chocolate.

Favorite way to relax?

Riding my horse. It’s meditative for me. It’s the only way I know to turn off my thoughts.

Favorite thing you’ve bought this year?

A vacation — appreciated all the more after two years of COVID precautions!

In partnership with Ohio Third Frontier, The Ohio State University, Medtronic, Cardinal Health, Battelle and Huntington Bank, NIT worked with entrepreneurs and scientists to invest in, develop and commercialize neuroscience technologies to further their clinical application. Two successful companies were created during my time there (with novel therapies for chronic pain and overactive bladder). I also founded my own company, BehaviorCloud, which is still successfully operating.

That was all exciting, but I missed the thrill of testing new ideas in the lab. I started looking for a way to balance my interests.

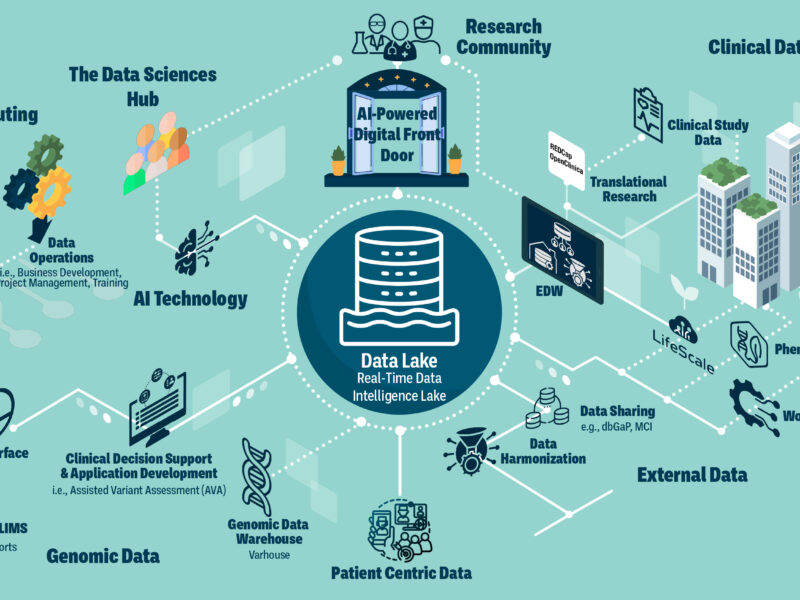

By a chance connection, I learned about new translational research in the Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine at Nationwide Children’s to detect brain mosaicism in patients with focal epilepsy — the perfect opportunity to combine my interest and expertise in mosaicism with my desire to engage in translational research to benefit patients.

I joined the Institute as a senior research scientist and obtained funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to identify brain mosaicism at the single-cell level. The following year, I started my own lab as a principal investigator to pursue research about the role of mosaicism in brain development and disease.

What is your favorite part of your job?

As a scientist, I get a thrill from looking at new data and thinking about how it fits into our existing knowledge and possibilities for the future. I also find it gratifying that I can help facilitate the success of the students and postdoctoral scientists in my lab as I lead my research program.

What’s next?

I hope our work leads to a better understanding of the genes involved in neurodevelopmental diseases so we can move toward treatments.

My lab has begun looking at the single cell level to compare patient cells with and without somatic mutations. We just published work in Brain based on findings from one patient, and we’ve started analyzing samples from others as well. We also use mouse models to study the effects of genetic mutations on disease onset, symptom severity or behavior. A new project in the lab will examine genetic mosaicism as a possible risk factor for post-traumatic epilepsy. Moving forward, we hope to understand how somatic mosaicism shapes the developing brain and translate our findings from specific genetic variants to the realm of targeted epilepsy therapy based on a patient’s unique genetic profile.

About the author

Katherine (Katie) Brind’Amour is a freelance medical and health science writer based in Pennsylvania. She has written about nearly every therapeutic area for patients, doctors and the general public. Dr. Brind’Amour specializes in health literacy and patient education. She completed her BS and MS degrees in Biology at Arizona State University and her PhD in Health Services Management and Policy at The Ohio State University. She is a Certified Health Education Specialist and is interested in health promotion via health programs and the communication of medical information.

-

Katie Brind'Amour, PhD, MS, CHEShttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/katie-brindamour-phd-ms-ches/April 27, 2014

-

Katie Brind'Amour, PhD, MS, CHEShttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/katie-brindamour-phd-ms-ches/April 27, 2014

-

Katie Brind'Amour, PhD, MS, CHEShttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/katie-brindamour-phd-ms-ches/April 27, 2014

-

Katie Brind'Amour, PhD, MS, CHEShttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/katie-brindamour-phd-ms-ches/April 28, 2014

- Posted In:

- Featured Researchers

- Research