Optimizing Prenatal and Neonatal Care for Infants With Treatable Rare Diseases

Optimizing Prenatal and Neonatal Care for Infants With Treatable Rare Diseases https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/020524BT517_FeatureHR-crop-1024x619.jpg 1024 619 Katie Brind'Amour, PhD, MS, CHES Katie Brind'Amour, PhD, MS, CHES https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Katie-B-portrait.gif- April 19, 2024

- Katie Brind'Amour, PhD, MS, CHES

As new treatments emerge and diagnostics improve, earlier interventions offer infants with rare metabolic and neurodegenerative conditions a future wildly different than ever before.

Not long ago, a diagnosis of molybdenum cofactor deficiency (MoCD) type A meant death before kindergarten.

Since the FDA approval of NULIBRY® (fosdenopterin) in 2021, however, children diagnosed with MoCD type A — an inherited metabolic disorder that results in severe developmental delay and neurological damage due to the accumulation of sulfites and S-sulfocysteine (SSC) in the brain — have hope for a significantly longer life.

If this intravenous (IV) drug is administered prior to serious brain injury, they may avoid significant intellectual and physical disability.

The trick? Getting the diagnosis and beginning treatment before significant damage has been done.

A Sibling’s Silver Lining

In 2018, Jeyad Asfour was born to parents Hanan and Mohammed. Within days of birth, he suffered seizures and went on to experience profound developmental delays.

After years of being told his symptoms were due to hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) during childbirth, Jeyad’s family moved to central Ohio. During an appointment at a Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Hanan insisted that the typical events leading to HIE had never happened when her son was born. She also mentioned that a niece had been diagnosed with a rare genetic condition that could cause symptoms like her son’s.

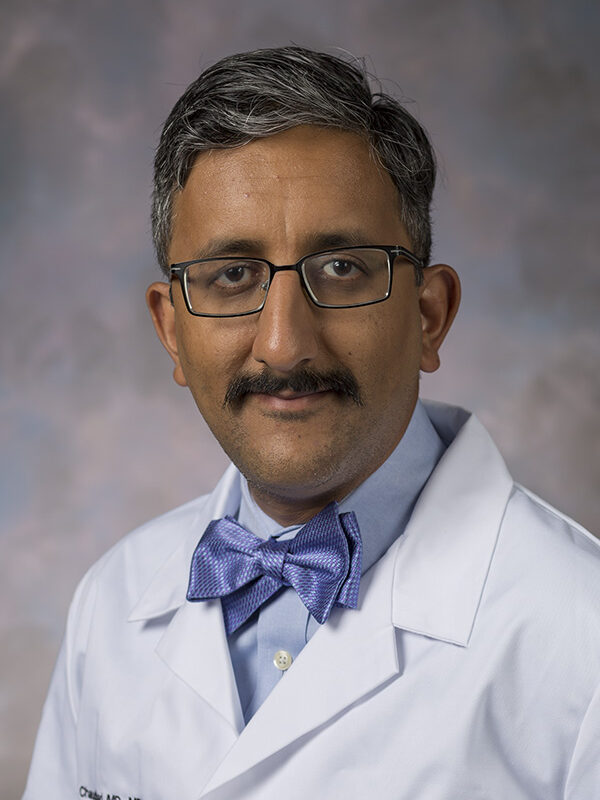

“A neurologist sent the family to me — I have a reputation for doing evaluations of babies in the NICU who have diseases that look like HIE,” says Bimal Chaudhari, MD, MPH, a neonatologist and genetics and genomic medicine specialist at Nationwide Children’s. “I took a look at the child’s records and said, ‘I’m sorry you’ve been told this, there’s no way your child has HIE,’ and we did genetic testing and got him the right diagnosis.”

The test revealed Jeyad had MoCD type A. Although there had been no treatment available for the condition when he was born, fosdenopterin had been approved by the time of his diagnosis. Finally, the family had an answer, a treatment and a way to prevent further neurodegenerative progression for Jeyad.

Fast-forward 2 years, and Hanan found out she was expecting another child. She was eager to proactively identify expectations for her new child’s health and contacted Jeyad’s geneticist to discuss a game plan.

The genetics and maternal-fetal medicine teams at Nationwide Children’s collaborated with Hanan’s obstetric experts at a local hospital system, Ohio Health, who confirmed that this sibling, another son, also had MoCD type A.

The news was devastating, but the early knowledge offered the family hope — and an opportunity to intervene before significant brain injury had begun.

Pioneering Management

Observable brain injury in cases of MoCD type A occurs during the third trimester, though from published literature it is unclear at exactly what gestational age the injury first emerges. For any given child, it is uncertain how significant the damage will be by the time of a full-term delivery.

The family’s growing care team within the Fetal Center at Nationwide Children’s — now comprised of maternal-fetal medicine, obstetrics, genetics, neurology, palliative care, a medical ethicist and neonatology specialists — discussed possible interventions.

“We explored the options, including whether we could get permission from the FDA for emergency use or set up a research study to try to give the fetus the drug in utero,” says Dr. Chaudhari. “But those all involved unknown risks, and there was no established way to give this drug before birth.”

Fosdenopterin requires daily IV treatments, rather than a one-time or periodic intervention, complicating things considerably. With fetal drug administration not being a viable option, the team explored the next-best opportunity to prevent significant brain injury.

“The best option available was to offer elective preterm delivery to reduce the time of exposure to toxicity in the brain, and provide the baby really early treatment,” says Adolfo Etchegaray, MD, chief of fetal medicine at Nationwide Children’s, who consulted on the case and explored opportunities for prenatal management.

The family and team thought long and hard about the risks and benefits of elective premature delivery, which — if done too early — can be fraught with health threats to multiple organs, especially the lungs.

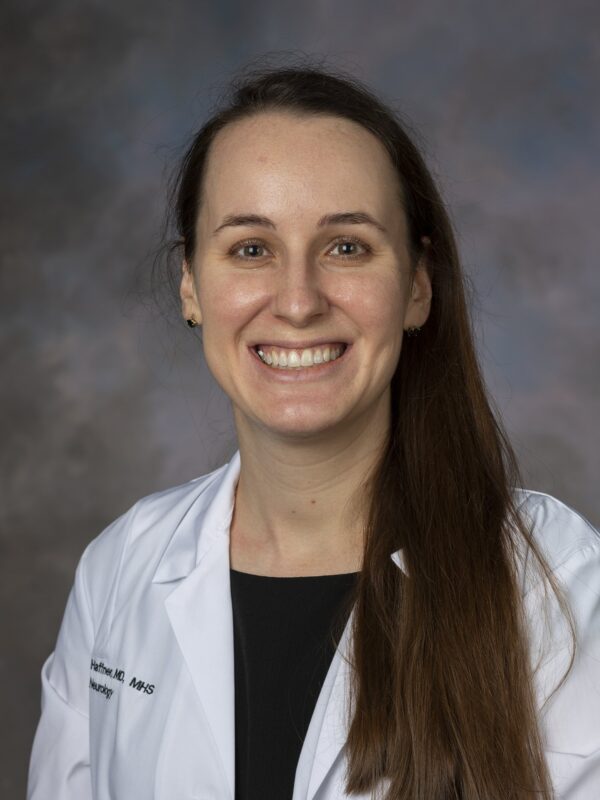

“We had a few multidisciplinary meetings to talk about at what point the risks of prematurity would be fairly low and when we might expect to see some injury occurring due to MoCD, since the family and the care team all wanted to deliver prior to any visible injury,” says Darrah Haffner, MD, MHS, an attending pediatric neurologist at Nationwide Children’s.

Based on her research, the literature suggested that damage could typically be visible on standard prenatal ultrasound — meaning it had already become significant, chronic cystic injury — by 35 weeks’ gestation.

“We knew we needed to precede that 35-week cut-off by at least a couple weeks to avoid that extensive injury,” says Dr. Haffner, “so we did serial MRIs in utero to track his development.”

The initial MRI, done at 22 weeks 5 days gestation, suggested fairly normal brain development. By 28 weeks 5 days, however, the team felt growing space behind the cerebellum was cause for concern. The images indicated potential mega cisterna magna, which is not specific to MoCD but is present in many cases of neurometabolic disorders.

“We know the earlier a child is born, the more likely they are to face lung immaturity, problems in the intestines and other complications of prematurity,” says Amy Schlegel, MD, director of the Perinatal Palliative Care Program and medical director of the NICU at Nationwide Children’s main campus. “We made every effort to choose that inflection point wisely, when we would be able to most positively impact the child’s neurologic outcome and still minimize the risks of prematurity. We settled on around 32 weeks knowing that at this gestational age, the risks of severe lung disease are lower, and babies are often large enough to tolerate feeding, EEGs and the medications they are likely to need.”

The team planned for a C-section at 32 weeks 6 days, with the procedure scheduled at Nationwide Children’s to allow the fastest administration of fosdenopterin and ongoing care in the NICU.

When Hanan came in a day early with concerns about reduced fetal movement, the operation began just ahead of schedule.

Making MoCD History

Baby Ghaith was born via an uncomplicated C-section on March 29, 2023. He received his first IV dose of fosdenopterin before he was 10 minutes old.

This administration within minutes of delivery is the earliest treatment of MoCD known to the Nationwide Children’s team.

“The one pharmacy in the country that stocks fosdenopterin isn’t in the habit of dispensing drugs to people who haven’t been born yet,” says Dr. Chaudhari. “It actually required an inordinate coordination of effort between pharmacy services, neonatal services, and fetal medicine to ensure the drug was available as soon after delivery as possible.”

Fosdenopterin works to reduce the toxic build-up of SSC in the brain by providing the missing component MoCD children need (cyclic pyranopterin monophosphate) to make molybdenum cofactor, which breaks down the sulfites and SSC. Theoretically, if it is administered before toxic accumulation, it should prevent acute injury to the brain. The sooner it is in a child’s system, the better the chance a child has to prevent new

damage — and its related seizures and symptoms — from occurring.

Ghaith experienced seizures starting about 12 hours after delivery, consistent with MoCD. By 36 hours after fosdenopterin administration, however, the seizures had ceased — something that rarely occurs even with appropriate seizure management in children with MoCD who do not receive fosdenopterin.

“Even doing all of these things, the baby still has some low level of brain injury, but it is worlds different than in kids without access to early treatment — such as his brother — and he was a little premature, after all,” says Dr. Chaudhari. “If you talk to Hanan and Mohammed, they’ll readily endorse the differences they see at this age for Ghaith compared to his older brother.”

Time will tell how effective the drug is over the long term, but initial follow-up suggests it is a game-changer when delivered prior to widespread brain injury.

Teasing Out the Impact

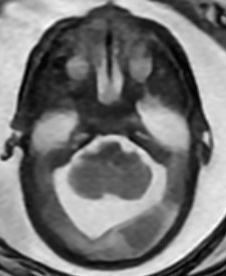

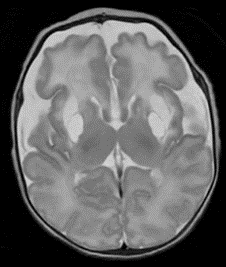

Ghaith’s initial postnatal MRI, done at 5 days of age, revealed that acute brain injury had indeed occurred following his 28 weeks 5 days gestational age MRI; the basal ganglia demonstrated new damage compared to his prenatal scans.

Injury to this area of the brain is frequently associated with muscle or motor skill delays. Sure enough, Ghaith displayed muscle tone abnormalities during his time at the NICU, and has since been diagnosed with cerebral palsy.

By about 5 weeks of age, however, just before his discharge from the NICU, Ghaith’s repeat MRI revealed astonishing news — unheard of for children with untreated MoCD.

“We could see where he had developed permanent cystic change from the prior injuries to the basal ganglia,” says Dr. Haffner, “but there was no new acute, ongoing injury. That’s real success, the fact that we were able to stop the injury where it was and it didn’t spread to the back parts of his brain,

and all over — that’s a really good thing.”

Provided the drug continues to work so well, the team expects to have halted the neurometabolic effects of Ghaith’s MoCD. This means early delivery and drug administration may have prevented debilitating developmental delays and even premature death for this little boy.

“I would be cautiously optimistic about what this case represents, in that I see this as an example of what an innovative team can do for a family in a difficult situation,” says Dr. Chaudhari.

As of one year of age, his cerebral palsy remains Ghaith’s only noticeable delay.

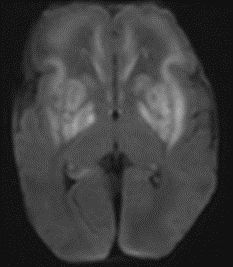

Serial Prenatal MRIs

The initial MRI (22 weeks’ gestation) showed largely normal development. Follow up at 28 weeks revealed potential mega cisterna magnum, or increased space behind the cerebellum. Although the volume was not worrisome yet, it is a common feature of MoCD. The care team believed it suggested emerging injury.

Postnatal MRI at 33 weeks 3 Days Gestational Age Equivalent (day 5 postnatally)

Postnatal MRI revealed acute injury to the basal ganglia (white areas in the top images) occurred between 28 weeks’ gestation and birth.

While the drug has not existed long enough to study its long-term impact, data from other recipients suggest varying degrees of helpfulness — most likely due to varying degrees of existing brain damage prior to treatment. The Nationwide Children’s team is optimistic that early intervention changed the trajectory of Ghaith’s life.

“When he went home from the NICU, we could already potentially predict some motor differences down the road for him,” says Dr. Schlegel. “But I also suspect that, had we allowed another 2 months in utero, that injury would have been much more significant. I know we did something to change Ghaith’s outcome, and we are going to continue to support healthy outcomes for him through nutrition, medicine, and occupational and physical therapy for a long time to come.”

A Brighter Outlook for Children With Rare Neurometabolic Diseases

As the damage had not noticeably progressed on his follow-up MRI, and there have been no clinical indications of new MoCD-related symptoms, Ghaith’s ongoing care will consist only of physical and occupational therapy, daily at-home fosdenopterin, and periodic neurologic and genetic follow-up visits at Nationwide Children’s.

“This has become one of my favorite patient stories because of how collaborative we were with the family and our teams in making recommendations, how carefully we pulled in specialists with expertise in ethics, obstetrics, palliative care and neurology throughout the case,” says Dr. Schlegel. “I know we did the right things for this baby and thoughtfully came together to change the outlook for him.”

At Nationwide Children’s, this type of early identification and bespoke intervention is par for the course. Although prenatal identification of rare genetic disorders often occurs only among cases such as Ghaith’s, where a prior sibling or family member has already undergone a diagnostic odyssey or the mother has elected to undergo prenatal testing, the technology available for rapid, early diagnosis is dramatically more advanced — and rapid — than in years past.

“We’ve reduced the time it takes to get a diagnosis by about 90% or more in the last decade, so much so that we can make a diagnosis on a research basis in just 30 hours or so if there is a sick baby,” says Dr. Chaudhari. “When neonatologists hear that, suddenly they are willing to pursue early diagnostics. And if those diagnostics happen, suddenly treatments become viable.”

As diagnosis begins to precede irreversible brain damage, treatments begin to have the opportunity to prevent injury, making the entire cycle of testing and intervention more worthwhile.

“If we can diagnose early,” explains Dr. Chaudhari, “a lot of things that used to be untreatable suddenly become treatable.”

Dr. Chaudhari and Dr. Haffner both specialize in identifying alternative explanations for delays and disabilities experienced by babies who spent time in a NICU. Such children often receive the label of HIE with little formal investigation into the possibility of other conditions that can mimic that pattern of brain injury.

“It’s the bread and butter of what I do,” says Dr. Haffner. “We can’t automatically say it’s hypoxic ischemic injury, and I’m very passionate about that. When the case is subtle or questionable, we have to look at other things that could be mimicking those symptoms, especially now that we have therapies for things like MoCD — we could treat and change the course of these diseases.”

For diseases with effective new therapies, it may even make sense to extend screening beyond families with a known history of a disease to the broader population via newborn screening or prenatal genetic testing.

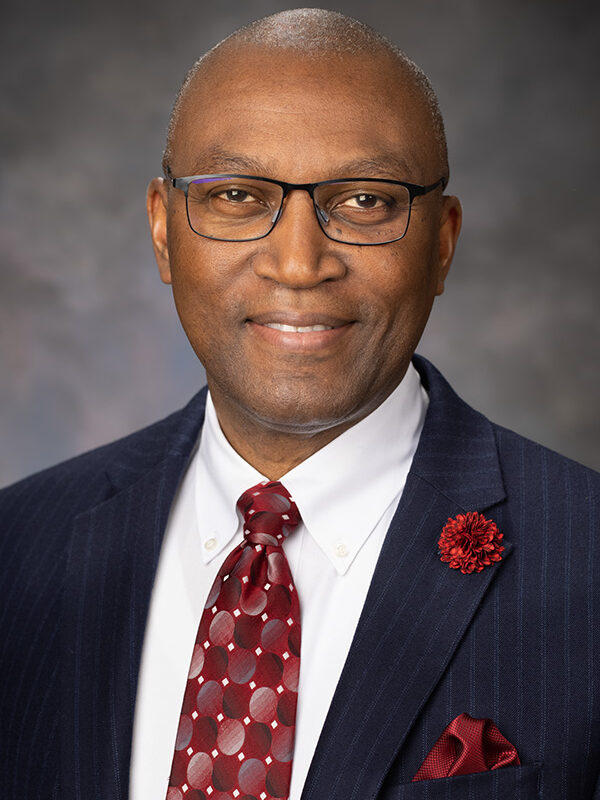

“We need to improve opportunities for prenatal testing to identify conditions,” says Oluyinka Olutoye, MD, surgeon-in-chief and a world-renowned neonatal and fetal surgeon at Nationwide Children’s. “Now that there is ever-growing potential to intervene medically before a child is born, it expands the utility of prenatal testing. When a diagnosis is made earlier, we can find ways to intervene earlier to improve outcomes.”

Reimagining the Future of Genetic Disease Therapies

Better still than early identification with immediate postnatal treatment, as in Ghaith’s case, would be therapy while a patient is still in utero.

“As great as is to be able to treat the baby, the world really needs to start thinking fetal,” says Dr. Chaudhari. “We need to get better at translating neonatal interventions into fetal interventions so that we aren’t delivering prematurely. It was the best we could do for their family in that moment, but it’s not what we should be striving for long-term.”

While this was not available for Ghaith, it may become possible for others with a wide variety of genetic disorders and other rare conditions.

“The speed of genomics is starting to give us opportunities to intervene earlier and earlier both postnatally and prenatally,” says Dr. Etchegaray. “We have that capability, and it’s certainly an advantage being at a place where many of the new gene therapies are actually being developed — we see genetics not only as a way of understanding a diagnosis, but as a potential tool to correct that problem.”

“This case is a harbinger of what’s possible,” says Dr. Olutoye. “It shows what can be done to change the trajectory of health for our patients, to improve outcomes for infants and children.”

The Fetal Center team at Nationwide Children’s already intervenes before birth for a whole host of complicated diagnoses, including structural heart anomalies and spina bifida. These prenatal interventions allow the tiny patients life-altering and potentially life-saving changes in their health conditions early, to reduce the risk for ongoing development.

“I’m really excited regarding what is to come in maternal-fetal medicine,” says Dr. Etchegaray. “We can open our menu of interventions for thousands of

conditions for which we would be able to provide really personalized medicine, treat exactly one gene, protein or pathway with a customized recipe instead of treating at the level of the entire target organ.”

This ideal is something the broader teams at work behind the scenes of Ghaith’s care hope to achieve for a growing number of rare diseases and complicated diagnoses. Dr. Olutoye expects to see more successes like Ghaith’s as Nationwide Children’s and other leading institutions fine-tune early diagnosis, treatment development and proactive, personalized intervention plans for children with rare diseases.

This article appeared in the Spring/Summer 2024 issue. Download the full issue.

Image credits: Nationwide Children’s

This case has been submitted for publication.

About the author

Katherine (Katie) Brind’Amour is a freelance medical and health science writer based in Pennsylvania. She has written about nearly every therapeutic area for patients, doctors and the general public. Dr. Brind’Amour specializes in health literacy and patient education. She completed her BS and MS degrees in Biology at Arizona State University and her PhD in Health Services Management and Policy at The Ohio State University. She is a Certified Health Education Specialist and is interested in health promotion via health programs and the communication of medical information.

-

Katie Brind'Amour, PhD, MS, CHEShttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/katie-brindamour-phd-ms-ches/April 27, 2014

-

Katie Brind'Amour, PhD, MS, CHEShttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/katie-brindamour-phd-ms-ches/April 27, 2014

-

Katie Brind'Amour, PhD, MS, CHEShttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/katie-brindamour-phd-ms-ches/April 27, 2014

-

Katie Brind'Amour, PhD, MS, CHEShttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/katie-brindamour-phd-ms-ches/April 28, 2014

- Posted In:

- Features

- Patient Story