Understanding the Social Neural Network

Understanding the Social Neural Network https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/AdobeStock_77919065-kid-brain-header-1024x575.gif 1024 575 Natalie Wilson Natalie Wilson https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Natalieheadshot3-2.png- July 06, 2021

- Natalie Wilson

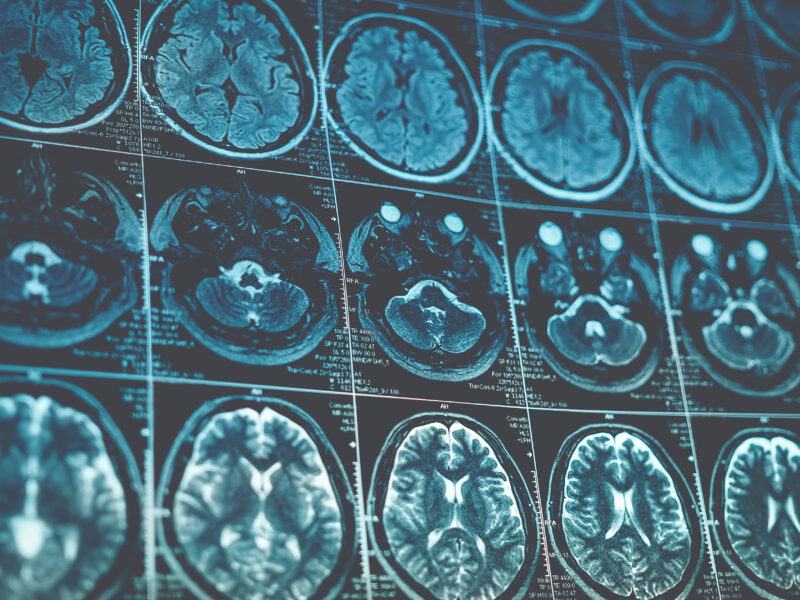

Neuroimaging of participants with and without epilepsy allows researchers to explore the neural networks associated with social skills.

Epilepsy is a chronic brain disease characterized by neural network dysfunction and seizures. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 470,000 children in the United States had active epilepsy in 2015.

These children are more likely to have difficulties with social interactions compared to their peers. Researchers in the Center for Biobehavioral Health in the Abigail Wexner Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital hypothesized that this may be due in part to disruptions to the organization of neural networks that guide social cognition. A recent publication in Neuropsychologia describes their investigation of this hypothesis.

“There’s been a lot of interest in the brain’s processes — in defining the networks that link areas for certain tasks, identifying how regions talk to each other and transfer information, understanding how these networks develop and mature, etc. — particularly in people with disorders like epilepsy,” says Eric Nelson, PhD, a principal investigator in the center and senior author of the study.

While previous studies have identified structural abnormalities and reduced connectivity in neural networks across the brain among patients with epilepsy, none have specifically focused on those circuits relevant to social cognition or social behavior in children. Yet successfully navigating social interactions requires that many areas across the brain that can be impacted by epilepsy communicate effectively: those responsible for identifying facial expressions, interpreting nonverbal signals, understanding motivation, inhibiting impulsive behavior, utilizing working memory, processing emotions, marking encounters and gestures as noteworthy and more.

Two key circuits that connect these areas are the “mentalizing network,” which helps individuals perceive and interpret the emotional states of others using auditory and visual cues, and the “amygdala network,” which is involved in processing one’s own emotional responses to salient social situations.

Dr. Nelson and a team of researchers led by postdoctoral fellow Michele Morningstar, PhD, who is now an assistant professor of Psychology at Queen’s University, used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans to record the brains of participants with and without epilepsy while they were relaxing normally and while they were engaged in a facial emotion recognition task to examine activity along these networks.

They found that the brain connectivity of participants with epilepsy differed from participants with typical development (TD) when both groups were completing a facial emotion recognition task but not when they were resting, suggesting that epilepsy — or frequently comorbid conditions, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) — may have a greater impact on circuits involved in social tasks than on resting-state systems.

“This approach is a first step towards concretely defining the specific social problems faced by children with epilepsy and what underlies them,” says Dr. Nelson, who is also a professor of Pediatrics at The Ohio State University College of Medicine. “Which networks aren’t functioning? Could neurological medications impact them? We can develop clinical guidance for minimizing impairment and managing this aspect of the condition long-term. That has significant implications for these patients’ quality of life.”

While the study team found participants with epilepsy experienced less brain connectivity along both networks compared to TD participants during the facial emotion task, their MRI scans showed greater connectivity within the temporal lobe, suggesting this group’s brains may have relied more heavily on areas of the brain involved in mentalizing to compensate for weaker long-range connections to other relevant regions. This pattern of connectivity was less efficient, however, and correlated with a poorer ability to identify the faces in the study.

A secondary analysis of the study data also showed age-related differences in connectivity. When completing the facial emotion recognition task, participants with epilepsy showed different patterns of age-related changes in neural connectivity in their brains compared to TD participants. This suggests that the typical maturation of neural network connectivity across childhood and adolescence in TD youth may also be disrupted in children with epilepsy, an idea that’s compatible with previous research showing social cognitive deficits are more pronounced in adults who have had epilepsy since childhood.

The study authors believe one possible explanation for these age-related differences in connectivity could be that the brains of participants with epilepsy had deactivated these networks during repeated seizures as a protective mechanism to limit their spread across the brain, causing the networks to atrophy. However, just as in the primary analysis, though the neural connectivity in participants with epilepsy did not become more fine-tuned with age compared to TD participants, certain regions of their brains did appear to become increasingly activated with age — again suggesting that compensatory reorganization of neural networks may occur in children with epilepsy.

“Epilepsy is a complicated disease. Seizures themselves cause damage to neural networks, but people with complex comorbid pathologies also often develop epilepsy,” says Dr. Nelson.

This means, Dr. Nelson explains, that epilepsy could reduce neural connectivity, reduced neural connectivity could be a risk factor in developing epilepsy, or these patterns could even be the result of a third variable: frequently comorbid conditions like ASD.

“It’s difficult to understand whether there is a causal interaction,” he adds.

He and his team consider these findings a first step and note that larger-scale, longitudinal studies that consider age are needed to further tease out the potential brain-based mechanisms of social deficits in youth with epilepsy. Next, they plan to examine network organization more broadly across development among these patients over the course of their lives.

“This study demonstrates the feasibility of using our study design comparing resting-state connectivity to functional task connectivity to explore a variety of clinical phenotypes in epilepsy, as well as overall brain development in both TD children and children with chronic disease,” says Dr. Nelson.

Reference:

Morningstar M, French R C, Mattson W I, Englot D J, Nelson E E, Social brain networks: Resting-state and task-based connectivity in youth with and without epilepsy, Neuropsychologia. 2021 Jul 16;157:107882. Epub 2021 May 5.

Image credit: Adobe Stock

About the author

Natalie is a passionate and enthusiastic writer working to highlight the groundbreaking research of the incredible faculty and staff across Nationwide Children's Hospital and the Abigail Wexner Research Institute. Her work at Nationwide Children's marries her past interests and experiences with her passion for helping children thrive and a long-held scientific curiosity that dates back to competing in the Jefferson Lab Science Bowl in middle school. Natalie holds a bachelor’s degree in sociology from Wake Forest University, as well as minors in women's, gender & sexuality studies and interdisciplinary writing. As an undergraduate student, Natalie studied writing and journalism, engaged with anthropological and sociological research with a focus on race and ethnic relations, served as executive editor for the student newspaper, the Old Gold & Black, and gained marketing experience as an intern for a nonprofit entrepreneurial incubator, Winston Starts, as well as by working for Wake Forest University School of Law Office of Communication and Public Relations and its Innocence and Justice Clinic.

-

Natalie Wilsonhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/natalie-wilson/

-

Natalie Wilsonhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/natalie-wilson/

-

Natalie Wilsonhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/natalie-wilson/

-

Natalie Wilsonhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/natalie-wilson/