Do Warning Labels on High-Powered Magnets Prevent Child Injury?

Do Warning Labels on High-Powered Magnets Prevent Child Injury? https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/AdobeStock_51092262-1024x521.jpeg 1024 521 Laura Dattner Laura Dattner https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/LauraDattner-web-002.jpg- October 05, 2022

- Laura Dattner

A recent study suggests parents often don’t notice or read warning labels on high powered magnets. They also perceive these products as children’s toys, despite FDA rules against marketing them to children under age 14 years.

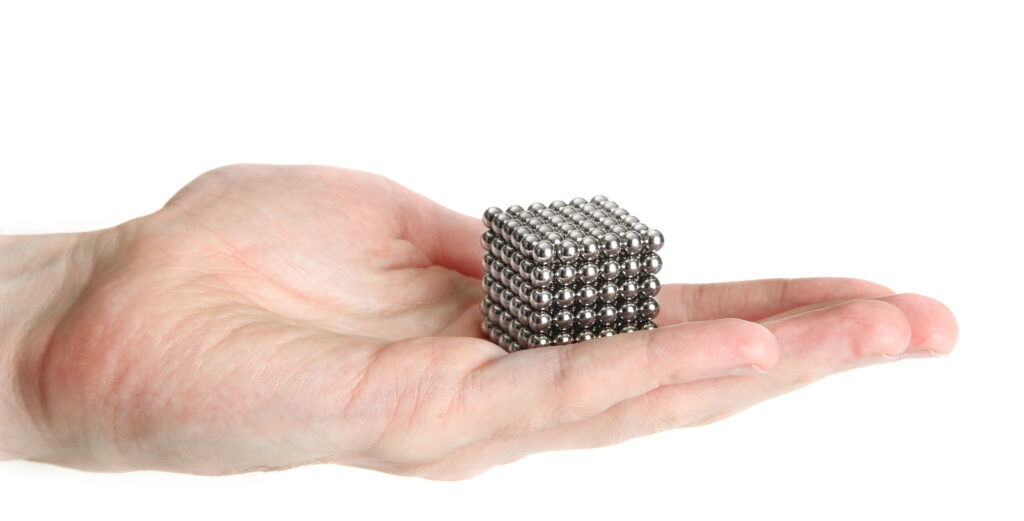

High-powered magnet products are made of rare-earth metals, usually neodymium, that is up to 30 times more powerful than the average refrigerator magnet. They are among the most dangerous childhood foreign body exposures in children due to the strength with which they attract to each other across human tissue. When high-powered magnets are swallowed by children, for example, the magnets can connect across the intestine, cutting off blood supply and killing the tissue.

High-powered magnet sets were effectively banned by the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission from 2014 to 2016 due to the numerous injuries and deaths in children. In 2016, the ban was overturned by a federal court, allowing high-powered magnets back on the U.S. market as long as the product is marketed to consumers over 14.

In the years after high-powered magnet sets were reintroduced to the market, there has been a significant increase in related injuries. Consumer advocates and physician groups called for these products to again be effectively banned, while U.S. manufacturers asserted warning labels are sufficient to mitigate risk.

Concerned pediatric specialists from across the country joined together to better examine high-powered magnet injuries in children. This research group is called the IMPACT of Magnets Research Collaborative, led by Leah K. Middelberg, MD, pediatric emergency medicine physician at Nationwide Children’s Hospital.

The IMPACT of Magnets Research Collaborative looked at children from birth to 21 years old who were seen for a high-powered magnet exposure at 25 participating children’s hospitals from 2017 through 2019. As part of this study, medical records of these children were retrospectively reviewed, and then researchers prospectively contacted families to capture their attitudes and beliefs around magnets, specific product data such as the manufacturer name and presence or absence of warning labels, and circumstances surrounding any injuries.

The paper, published in Pediatrics in October 2022, presents the findings of the prospective surveys.

The IMPACT of Magnets cohort includes 596 patients and researchers were able to contact 174 of those patients or parents. There was no statistical difference between patient characteristics of those who consented to interviewing and the rest of the cohort.

Of the 174 patients included, the median age was 7.5 years old, approximately half the intended age for these products. Almost half of respondents believed high-powered magnets are children’s toys. The majority of parents reported knowing high-powered magnets were dangerous prior to the incident, but only 7% knew they were removed from the market for a period of time by the CPSC. This suggests that parents may underestimate their child’s vulnerability to high-powered magnet ingestions.

“Given the emphasis of warning labels as a mitigation measure in high-powered magnet injuries, we asked parents and patients their perceptions of warning labels and their effectiveness,” says Dr. Middelberg. “We found that only one in four respondents reported a warning label was present on the high-powered magnet product involved, though less than half of those reported reading it.”

Additionally, only 18% reported products were stored in their original containers.

Approximately 90% of subjects didn’t know if warning labels were present, failed to read them if they were, or stated there was not one present. Warning labels on high-powered magnet products are therefore unlikely to prevent injuries in children.

Limitations of this work include a relatively limited sample size, since many families could not be reached. Results may also be limited by recall or reporting biases, in which parents may forget details of their experience years earlier or selectively report details based on that experience. And lastly, the study is limited by selection bias, as this study was only performed in children’s hospitals and may be influenced by referral patterns.

In September 2022, the United States CPSC approved a new Federal Safety Standard for magnets to prevent deaths and serious injuries from high-powered magnet ingestion. The new mandatory federal standard requires “loose or separable magnets in certain magnet products to be either too large to swallow, or weak enough to reduce the risk of internal injuries when swallowed; specifically, if the magnets fit in a small parts cylinder, then they must have a flux index of less than 50 kG2 mm2.”

According to a press release from the CPSC, “The new rule applies to consumer products that are designed, marketed, or intended to be used for entertainment, jewelry (including children’s jewelry), mental stimulation, stress relief, or a combination of these purposes, and that contains one or more loose or separable magnets. It does not include products sold and/or distributed solely to school educators, researchers, professionals, and/or commercial or industrial users exclusively for educational, research, professional, commercial, and/or industrial purposes. The new rule does not apply to toys for children under 14 years old, because the CPSC’s mandatory toy standard (16 CFR part 1250) already covers such products.”

Reference:

Middelberg LK, Leonard JC, Shi J, Aranda A, Brown JC, Cochran CL, Eastep K, Haasz M, Hoffmann JA, Koral A, Lamoshi A, Levitte S, Lo YHJ, Montminy T, Myer S, Novotny NM, Parrado RH, Ruan W, Stewart AM, Talathi S, Tavarez MM, Townsend P, Zaytsev J, Rudolph B. Warning Labels and High-Powered Magnet Exposures. Pediatrics. 2022 Oct 3:e2022056325. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-056325.

Image credit: Adobe Stock

About the author

Laura Dattner, MA, is a research writer in the Center for Injury Research and Policy of the Abigail Wexner Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. With both a health communications and public health background, she works to translate pediatric injury research into meaningful, accurate messages which motivate readers to make positive behavior changes.

-

Laura Dattnerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/laura-dattner/

-

Laura Dattnerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/laura-dattner/April 4, 2019

-

Laura Dattnerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/laura-dattner/

-

Laura Dattnerhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/laura-dattner/