Growth Hormone is Still Important Beyond the Growing Years

Growth Hormone is Still Important Beyond the Growing Years https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/101916BS0020_1-1024x683.jpg 1024 683 Rohan Henry, MD, MS Rohan Henry, MD, MS https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/080719ds2553-crop.jpg- May 12, 2021

- Rohan Henry, MD, MS

The History of Growth Hormone

The first reported use of growth hormone (GH) as treatment for severe growth retardation occurred in the 1950s.1 Since that time, growth hormone’s importance in growth promotion has been clear. Its role in promoting normal metabolism even after growth has ended, however, was only recognized in the late 1980s.2

Beginning in the 1950s, the initially administered pituitary growth hormone (pit-GH) product was derived from cadavers. This resulted in a limitation in supply relative to demand for the product. A height cap was established in the United States, which allowed only the shortest individuals to be treated with pit-GH in the 1960s.3 Research about growth hormone’s positive metabolic effects and its role beyond growth promotion continued.

As with many events in clinical practice, serendipity played a part in the evolution of GH to its current form. In 1985 after four individuals who received growth hormone in childhood (three in the United States and one in Canada) developed an encephalopathy from pit-GH, its production was abruptly terminated.3 Though growth hormone production by recombinant DNA technology had been studied prior, its approval at that exact time by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is seen as fortuitous.

Evidence for the Metabolic Effects of Growth Hormone

With an increased supply generated by a new source, it was evident that GH supplementation could ameliorate metabolic concerns evident during the natural history of patients with severe and untreated growth hormone deficiency (GHD).

Because of the previously limited supply of GH, it had not been possible to conduct trials surrounding its metabolic benefits, despite speculation that a GHD syndrome was evident in patients with severe GHD who were not supplemented after linear growth ended.

Finally, in 1987 recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) was approved for adults with a history of newly diagnosed or acquired diseases of the pituitary gland or hypothalamus based on the actual recognition that a distinct GHD syndrome could develop in its absence.2 This syndrome includes reduced psychosocial wellbeing and decreased bone mineral density which can be accompanied by body composition and metabolic abnormalities.4,5

Information from both basic sciences and clinical medicine support the importance of GH in the well state. In the global GH receptor knock out mice model, inflammation, liver fibrosis, fatty liver and liver tumor develop. GH also has a positive impact on insulin production in some mouse models.6

In men with hypopituitarism (absence of thyroid hormone, cortisol, testosterone and growth hormone), fatty liver develops at baseline in the absence of GH replacement and can be reversed with GH therapy.7 The exact time during which metabolic issues can arise secondary to GHD is not clear; however, its effect on lipid and glucose metabolism is profound.8

Severe GHD that develops in children is distinct from GHD that begins in adulthood based on the adverse metabolic issues. In studies where GH supplementation is discontinued in adolescence for a period of two years after linear growth has ceased, important cardiovascular risk factors develop. These include an increase in total and LDL-cholesterol and a decrease in HDL-cholesterol.9 There has also been a relationship between adverse lipid profile and the period of interruption of GH therapy in childhood and adolescence: the longer the period of interruption of GH therapy, the greater the likelihood of developing adverse metabolic consequences such as lipid abnormalities.10

GH also impacts bone-mineral density and muscle mass positively. When compared to patients without severe GHD, those with untreated severe GHD have lower bone mineral density and muscle mass.9,11

While some studies show beneficial effects of GH on metabolism including effects on lipid profile, bone mineral density and general quality of life in some studies, other studies have not shown a beneficial effect of supplementation after growth plate closure.

In some of the latter studies the observation period after discontinuing GH may have contributed to the absence of positive findings. It is presumed that the period of time during which GH may have been discontinued may be too short to see the metabolic changes in some of these studies with findings which lack the positive effects associated with supplementation.

Do All Patients With Growth Hormone Deficiency Need Growth Hormone After Completing Growth?

Because GH clearly has benefits for many individuals, each child diagnosed with GHD should be evaluated to determine the permanence of the condition after linear growth has ended. Once permanence is established, it is important to properly transition these patients to adult GH dosing.

Though the impact of GH supplementation in reversing many metabolic abnormalities is far from clear, long term studies are especially needed to establish whether changes seen in childhood-onset GHD are permanent. Considering that there may be adverse metabolic outcomes of some individuals with untreated GHD, clinicians should be aware of the adverse metabolic consequences which may occur with untreated GHD and advocate for supplementation in patients who have a permanent deficiency.

References:

- Raben MS. Treatment of a Pituitary Dwarf with Human Growth Hormone. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1958;18(8):901-3.

- Geffner ME. Growth hormone replacement therapy: transition from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009;1(5):205-208.

- Frasier SD. The not-so-good old days: working with pituitary growth hormone in North America, 1956 to 1985. Journal of Pediatrics. 1997;131(1 Pt 2):S1-4.

- Jorgensen JO, Pedersen SA, Thuesen L, Jorgensen J, Ingemann-Hansen T, Skakkebaek NE, et al. Beneficial effects of growth hormone treatment in GH-deficient adults. Lancet. 1989;1(8649):1221-1225.

- Salomon F, Cuneo RC, Hesp R, Sonksen PH. The effects of treatment with recombinant human growth hormone on body composition and metabolism in adults with growth hormone deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;321(26):1797-1803.

- Fan Y, Fang X, Tajima A, Geng X, Ranganathan S, Dong H, et al. Evolution of hepatic steatosis to fibrosis and adenoma formation in liver-specific growth hormone receptor knockout mice. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2014;5:218.

- Nishizawa H, Iguchi G, Murawaki A, Fukuoka H, Hayashi Y, Kaji H, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adult hypopituitary patients with GH deficiency and the impact of GH replacement therapy. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2012;167(1):67-74.

- Adams LA, Feldstein A, Lindor KD, Angulo P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among patients with hypothalamic and pituitary dysfunction. Hepatology. 2004;39(4):909-914.

- Johannsson G, Albertsson-Wikland K, Bengtsson BA. Discontinuation of growth hormone (GH) treatment: metabolic effects in GH-deficient and GH-sufficient adolescent patients compared with control subjects. Swedish Study Group for Growth Hormone Treatment in Children. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1999;84(12):4516-24.

- Koltowska-Haggstrom M, Geffner ME, Jonsson P, Monson JP, Abs R, Hana V, et al. Discontinuation of growth hormone (GH) treatment during the transition phase is an important factor determining the phenotype of young adults with nonidiopathic childhood-onset GH deficiency. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;95(6):2646-2654.

- Ogle GD, Moore B, Lu PW, Craighead A, Briody JN, Cowell CT. Changes in body composition and bone density after discontinuation of growth hormone therapy in adolescence: an interim report. Acta Paediatric Supplement. 1994;399:3-7; discussion 8.

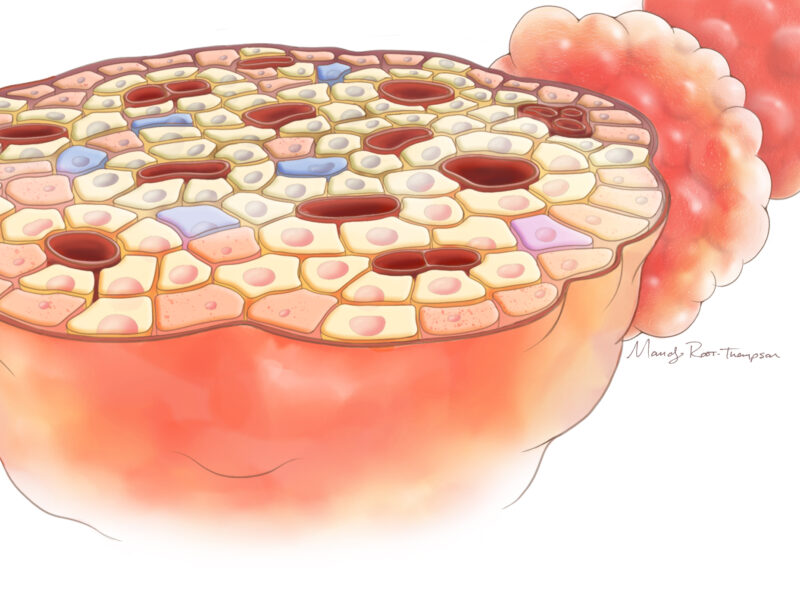

Image credit: Nationwide Children’s

About the author

-

This author does not have any more posts.

- Post Tags:

- Endocrinology

- Growth Hormone

- Posted In:

- Features

- Second Opinions