Stressed Out: Toxic Stress and Child Brain Development

Stressed Out: Toxic Stress and Child Brain Development https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/themes/corpus/images/empty/thumbnail.jpg 150 150 Dave Ghose Dave Ghose https://secure.gravatar.com/avatar/f146b259ebc8ba9d52ea9ef823792abf?s=96&d=mm&r=g- November 11, 2014

- Dave Ghose

Stress, in small doses, can be good for children. When they argue with another child over a toy or attend a new school or daycare, the experience can teach them valuable coping skills. Even a more intense event, such as the death of a loved one or a frightening accident, can be beneficial developmentally with the support of caring adults.

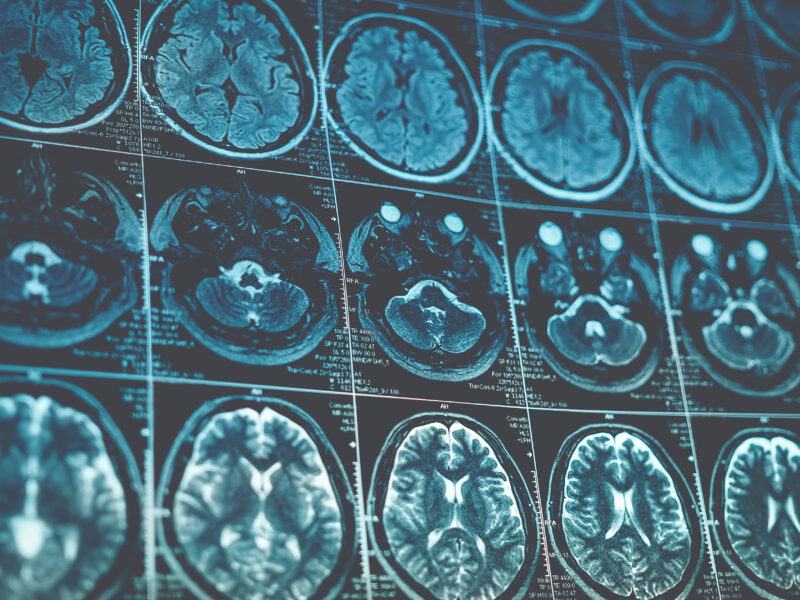

But what happens if the stress exposure lasts longer — days, weeks, months or even years? Research shows that this so-called “toxic stress” can lead to permanent neurological damage in children. “The brain architecture actually changes because of these exposures,” says Diane Abatemarco, PhD, MSW, associate professor of pediatrics at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

The phenomenon — often the byproduct of abuse, neglect and parental dysfunction — is becoming a growing public health issue. In June, the American Academy of Pediatrics hosted a Symposium on Child Health, Resilience & Toxic Stress in Washington, D.C., to discuss the lasting health impact of childhood adversity. Emerging science is driving the interest. Toxic stress, studies show, can lead to all kinds of long-term health problems, from diabetes and heart disease to depression and substance abuse.

Preventing toxic stress isn’t easy. Complex socioeconomic problems surround the issue. “Really, when you talk about toxic stress, you’re talking about poverty, you’re talking about parents who might have disabilities, who might not have economic resources,” says Dr. Abatemarco, who also is the director of pediatric population health research at Nemours Children’s Health System in Wilmington, Del.

But that doesn’t mean pediatricians are powerless. Dr. Abatemarco stresses the importance of universal screening tools such as SEEK, Bright Futures and Practicing Safety, which can help identify signs of toxic stress before too much damage is caused. She also advocates for including social workers and case managers in pediatric practices to better meet the needs of children and their parents.

Another effective measure can be mindfulness, says Dr. Abatemarco, whose research focuses on practical ways physicians can identify and prevent toxic stress. If pediatricians give their patients their full attention by listening with compassion and an open mind, they may notice things that can make a big difference. “When you’re more open, you’re going to see more of the real-life issues in that well-child visit,” she says.

- Post Tags:

- Behavioral Health

- Neurology

- Posted In:

- In Brief