How Primary Care Providers Can Help Justice-Involved Youth

How Primary Care Providers Can Help Justice-Involved Youth https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/082719ds1233-1-1024x683.jpg 1024 683 Deena Chisolm, PhD Deena Chisolm, PhD https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Chisolm2019Pic-profile.jpg- May 09, 2018

- Deena Chisolm, PhD

Deena Chisolm, PhD, shares how primary care physicians can support youth who may experience behavioral health issues related to justice involvement.

For most people in the United States, the law enforcement and criminal justice systems support a sense of safety and security. However, for some populations, particularly people of color, perceptions of and interactions with these institutions are not always positive. Fears of negative interactions with the juvenile justice system, experienced by many such youths and their parents generate a persistent stress that affects mental health and emotional well-being. Negative exposures to the juvenile justice system can leave young people scarred and scared.

Unfortunately, contact with the juvenile justice system is not rare. According to data from the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency, over 900,000 U.S. youths under the age of 18 were arrested in 2015, representing 1 in every 36 youths between the ages of 10 and 17. While this overall rate is disconcerting, disparities for boys (1 in 26) and African American youths (1 in 16) are alarming. The high incidence of juvenile justice involvement combined with research showing its associations with health and health care has led to studies of juvenile justice involvement as a socioenvironmental exposure that should be assessed and addressed in the health care system. But, what can or should providers be expected to do?

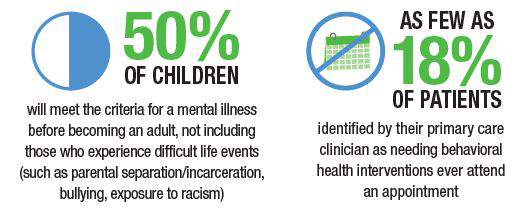

Glad you asked! Pediatric primary care systems can address mental and emotional health outcomes of juvenile justice involvement before, during and after an event. Of course, the best way to “treat” the negative mental and emotional health outcomes of juvenile justice involvement is to avoid the initial exposure altogether. Adolescent well-child visits provide an excellent venue to screen for and intervene upon behaviors such as fighting and substance use, which may lead to justice involvement. Timely referrals to behavioral health programs have the potential to address behaviors and their underlying causes before the police are engaged.

When an encounter can’t be avoided, the next best thing is to limit the damage. An important means of reducing risk during an encounter is “the talk,” an age-old conversation in the Black community, in which parents advise youths, particularly young men, about how to deescalate tensions and reduce the probability of a negative outcome when in direct contact with a law enforcement officer. While some in the pediatric community are advocating for primary care providers to offer a standardized clinical version of “the talk” as part of anticipatory guidance, there is a real risk of parents seeing this as usurping a key parenting role, especially when the clinician does not have a “lived experience” in which to base the content and the tone of the message. Instead, a helpful alternative would be for clinicians to offer resources to parents who want support in delivering the message and to reinforce the messages after parents and youths have talked.

Finally, we need to have a plan for caring for youth after a justice system encounter occurs. Whether it is as simple as a stop and warn or as major as a period of residential detainment, the exposure can leave a scar. Health care providers can help with healing. Providers who are aware of a youth’s juvenile justice involvement can screen for depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, substance use, social needs and family functioning in order to make referrals that address lingering stresses and reduce the risk of future justice involvement.

Early contact with juvenile justice is strongly associated with further and more serious involvement later in adolescence and into young adulthood. That further justice involvement is associated with poor educational attainment, unemployment and poverty, all known drivers of poor physical and mental health.

While some clinicians may argue that dealing with the problems generated by justice involvement goes beyond the scope of pediatric primary care, in reality, addressing the precursors and outcomes of this exposure has the potential to improve the health and well-being of children across their lifespan. Clinicians can make a positive difference in the clinical setting as described above, and, as importantly, they can bring their “white coat” influence out of the clinic and into the community. By engaging in community-level partnerships and policy-making, clinicians have the potential to help to develop solutions that foster healthy, safe and respectful interactions that promote mental well-being and, ultimately, trust.

About the author

Dr. Chisolm is the director of the Center for Innovation in Pediatric Practice at the Abigail Wexner Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and is an associate professor of Pediatrics at The Ohio State University College of Medicine and Public Health. She is a health services epidemiologist whose research is focused on measuring and improving the effectiveness, efficiency, and equity of pediatric health care.

Much of her current research is focused on the role of health care technology in improving pediatric health care quality. She is also interested in research investigating the factors associated with use of e-health services by at-risk youth. In addition, Dr. Chisolm serves as a resource to Nationwide Children’s Hospital clinical researchers on issues including: the use of clinical and administrative data in research, cost-effectiveness analysis, and quality indicator development.

-

Deena Chisolm, PhDhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/deena-chisolm-phd/April 24, 2017

-

Deena Chisolm, PhDhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/deena-chisolm-phd/July 2, 2020

- Posted In:

- Features