The Pediatrician’s Role in Health and Hope after Trauma

The Pediatrician’s Role in Health and Hope after Trauma https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/themes/corpus/images/empty/thumbnail.jpg 150 150 Anna Kerlek, MD Anna Kerlek, MD https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/091415bs182_AK-bio-pic.gif- May 08, 2018

- Anna Kerlek, MD

A primary care provider’s ability to identify and treat symptoms associated with trauma can increase positive outcomes for patients and families.

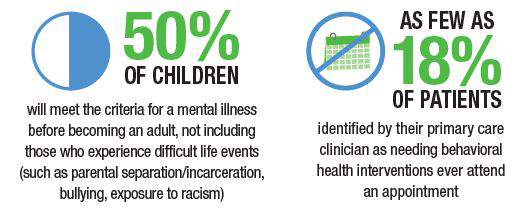

Almost two-thirds of the children and their caretakers in your office have experienced at least one trauma. Many have experienced more. As a primary care provider, you can provide early intervention and support for these families by knowing the signs and associated symptoms related to the effects of trauma.

Scientific evidence shows an association between exposure to traumatic events and long-term physical and mental health issues. Traumatic events include sexual, physical and emotional abuse, neglect, domestic and community violence, the loss of a caregiver and accidents. The trauma may be acute or the maltreatment ongoing. Alternatively, the trauma may be a series of historical events that are presenting now with concerning symptoms. The differential is broad, and one should recognize that trauma may be at the root of diverse symptoms such as developmental delays, ADHD-like symptoms, depression, anxiety and oppositional behavior. Very young children may appear easily frustrated, struggle with transitions, have intense tantrums and be slow to acquire milestones. Latency-age children may have difficulties with learning, fight with peers and appear to lie (which is perhaps them trying to fill in their memory gaps). Adolescents may engage in risky activities and have trouble keeping up with their schoolwork.

By helping families in this way, your practice can provide that glimmer of hope of their brighter future.

— Anna Kerlek, MD

First, Ask Questions

The above description likely fits more than half of the children you see each day. So, how do you sort it all out in one office visit?

Put simply, you don’t. This is why a medical home is ideal for long-term relationships, with meaningful evaluation and treatment over time. Of course, in acute crises, you will manage the situation in the moment by using your best clinical judgment to keep a child safe. But assessing a complex presentation in a child takes time and screening at every visit.

Screening for trauma should take place at every office visit, at every patient encounter. Remember, trauma experiences have happened to almost everyone, so it is our duty to ask about them. These conversations can be difficult to initiate and may feel out of your comfort zone, but you may change someone’s life trajectory. These conversations should include the following:

- Start by asking open-ended questions about stress or home-life changes.

- Follow up with direct, explicit and close-ended questions.

- Ask about abuse, exposure to violence and food insecurity.

- Preface questions by saying you ask all children and families these things (and if this practice is new in your office, say it is a new policy) to alleviate any feelings of being targeted.

Asking these questions helps you understand the symptoms the child may be experiencing and provides clues to the severity of symptoms and referral urgency. When considering whether a child may have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), screen for the following five clusters of symptoms:

- Intrusion symptoms, such as memories and dreams

- Avoidance symptoms

- Dissociative symptoms, such as feeling unreal or dazed

- Arousal symptoms, such as trouble sleeping or increased startle response

- Negative mood changes

Listening Is Your Most Powerful Tool

The act of listening is therapeutic in itself. As the physician, your initial response influences whether the family will seek further evaluation and treatment. When speaking with a patient or family about trauma, consider the following messages:

- Let them know it is not their fault and that you are there to help.

- Tell them you cannot fix it, or change what happened, but you will do everything you can to address their pain and safety now.

- Recommend appropriate psychosocial interventions.

As a pediatrician, you can recommend interventions that may help a family not to need outside referrals, or you may provide the necessary guidance while families await the recommended treatment.

What Are Appropriate Interventions?

Children and adults who have experienced repeated trauma are more at risk for longer-term mental and physical health problems. These children and families need you the most and can benefit from appropriate intervention.

Intergenerational trauma is common. Parents often suffer from their own symptoms, and you are in the unique position to link them with referrals, ideally in the same location as their child’s treatment. Most guardians can continue to care for their child in spite of their distress, but they may need help to do so.

Connecting Families to Services

It is important to remember that the vast majority of parents are doing their best, following the examples provided during their own childhoods. Families who have multiple adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) scattered throughout their family tree will likely need to be connected to other services. These serviced include:

- Crisis services for intimate partner violence

- Substance use treatment

- Food pantry locations

- Shelter options

- Financial counseling for health care

Evidence-Based Treatments

Evidence-based treatments are available to children and their families, offered at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and other agencies across the United States. Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) is the gold-standard individual therapy modality and Cognitive Behavioral Interventions for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) is a group treatment model for elementary and middle school children. Additionally, Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP) and Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) are often beneficial for these children and families.

For more information about treatment, and how to locate therapists locally, visit www.nctsn.org.

Medical Management

No medications are indicated to treat trauma or PTSD in children.

However, if severe, you may consider treating symptoms, such as insomnia or hyperarousal, with medication. I use the analogy of medicine being like training wheels that are necessary to help for a short time while the child learns life-long skills in therapy.

Providing Hope and Health

As you begin to address ACEs and trauma, you may feel like you are going beyond a pediatrician’s role. But by helping families in this way, your practice can provide that glimmer of hope of their brighter future.

With the passage of time and appropriate therapy, trauma will no longer define these children and caregivers. It will lose its power and become a manageable memory of bad experiences that they have confronted and mastered.

Recommended Resources:

About the author

Dr. Kerlek is a child psychiatrist specializing in the treatment of children who have experienced maltreatment and exposure to violence. She works at Nationwide Children's Family Support Program at The Center for Safety and Healing.

-

This author does not have any more posts.

- Posted In:

- Features