Intervention for Medically Complex Children Improves Health, Saves Money

Intervention for Medically Complex Children Improves Health, Saves Money https://pediatricsnationwide.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/061609bs155.jpg 800 533 Kevin Mayhood Kevin Mayhood https://secure.gravatar.com/avatar/bd57a8b155725b653da0c499ae1bf402?s=96&d=mm&r=g- April 24, 2017

- Kevin Mayhood

The population-based program features coordinated care, education and feeding tube management.

A population-based intervention for children with medical complexity in central and southeast Ohio led to fewer admissions, shorter hospital stays and a reduction of inpatient charges of nearly $11.8 million over 30 months, all while making children healthier. Nationwide Children’s Hospital and its affiliated accountable care organization, Partners For Kids (PFK), developed the quality-improvement effort, serving an average of 548 children each month, who had a neurological impairment and a percutaneous feeding tube and were covered by Medicaid.

The key steps were standardizing feeding tube management, improving family education and implementing a care coordination program within a framework that makes value of care rather than payment per service the financial incentive.

“Children with medical complexity are a challenge for families and the health care system, and they require a variety of people to help optimize their care,” says Garey Noritz, MD, chief of the Section of Complex Care at Nationwide Children’s and co-leader of the quality-improvement initiative. “We’ve found that if a system gets together and we say that we want to make a difference, we can.”

Nationally, these children comprise 6.9 percent of pediatric patients receiving Medicaid but consume 40 percent of the Medicaid budget spent on children.

“The United States spends an enormous amount of money on health care and a lot are questioning whether we are spending all that money well,” says Sean Gleeson, MD, president of PFK and co-leader of the initiative. “This work is focused on how can we design a system to care for each patient more effectively, give better clinical outcomes and do it in a way that requires less money.”

PFK, one of the country’s oldest and largest pediatric accountable care organizations, is a partnership between Nationwide Children’s and more than 1,000 doctors in central and southeastern Ohio to provide care for 330,000 children covered by Medicaid. Here, community-based approaches have improved outcomes.

Ohio’s Managed Medicaid plans pay a set amount per child, or capitation fee, up front to PFK. Nationwide Children’s and member physicians are then responsible for allocating that money effectively to make sure all of the covered children receive the care they need.

“Generally, the better the care, the less you spend on it. But you have to be organized,” Dr. Noritz says.

A study of the initiative is published in the January 2017 issue of Pediatrics.

To begin, patients were narrowly defined, which allowed for better tracking and reliable data. A variety of medical doctors, surgeons, nurses, neurologists, parents, administrators and dietitians were asked what would better care look like, what works, what are the current frustrations and more. As they developed the program, leaders rapidly adjusted the initiative to the realities they found.

Social workers or registered nurses were hired as care coordinators to help patients and their families navigate the health care system and reach goals delineated in each patient’s treatment plan. Coordinators contacted the families at least monthly and met in person every 90 days, reassessing and updating goals each quarter.

Much of the coordinated care focused on the feeding tubes. Because the apparatus requires maintenance, different procedures for usage and an individualized nutrition plan, “they’re a boondoggle for families,” Dr. Noritz says. “Lots can go wrong.”

Families were given structured, individualized training, including hands-on demonstrations and practice with mannequins.

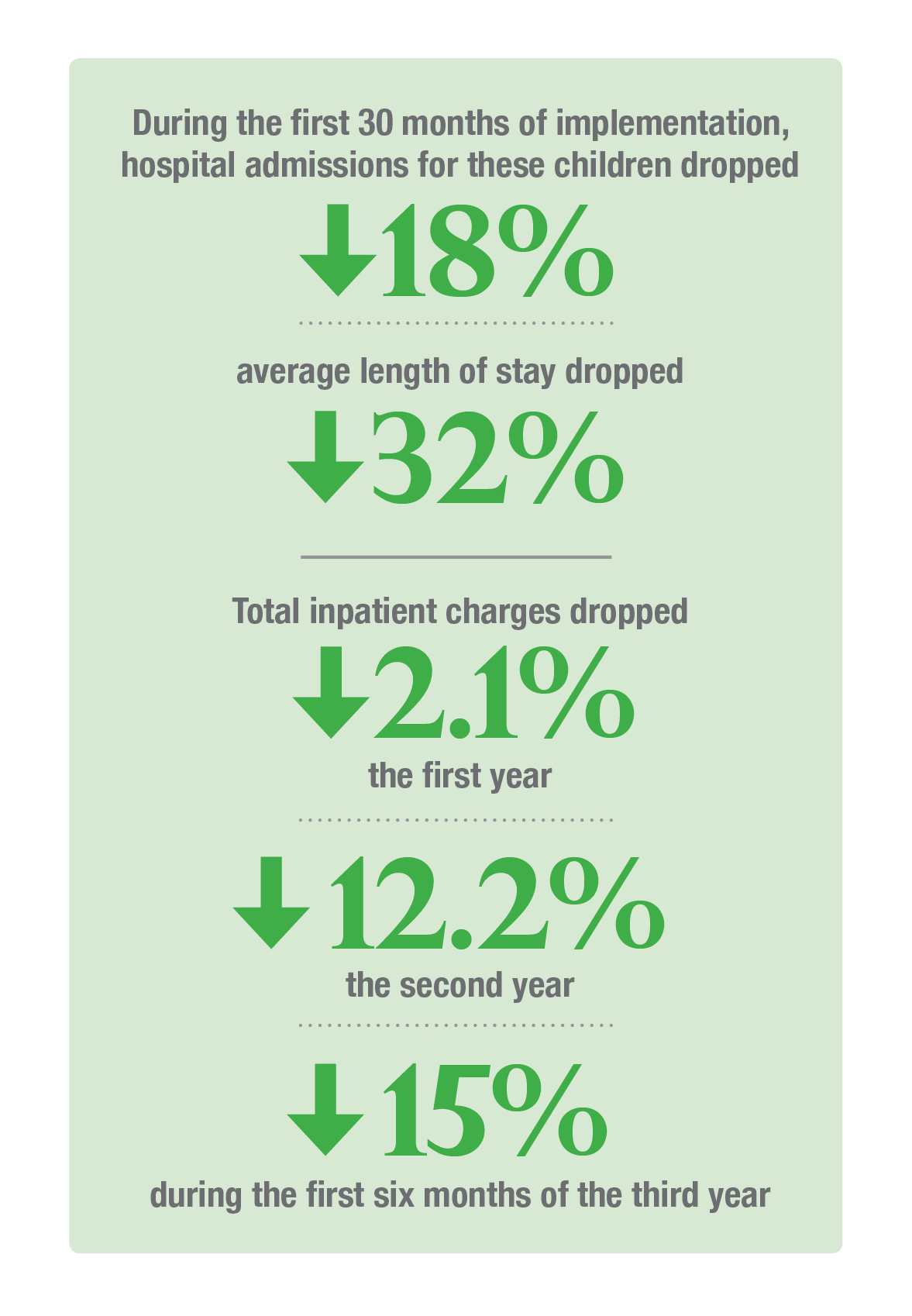

Between January 2011 and December 2014, care coordinators enrolled 58 percent of the target cohort. During the first 30 months of implementation, hospital admissions for these children dropped 18 percent and average length of stay 32 percent. Total inpatient charges dropped 2.1 percent the first year, 12.2 percent the second and 15 percent during the first six months of the third.

The percentage of children with weights between the 5th and 95th percentiles, an important health marker, increased 8.2 percent.

“It shows that when you shift the model from fee for service to value-based care, that can improve things as long as the incentives are aligned correctly,” Dr. Noritz says. “We incentivize better care, not more care.”

The initiative was jump started with a federal grant but making care more efficient allowed the system to create a funding source that keeps the work sustainable, Dr. Gleeson says. The people hired for care coordination under the grant are now paid for from the Medicaid capitation fees and more are being hired due to the initiative’s success.

“The bottom line is encouraging,” Dr. Gleeson says. “We spent a lot of time and effort on this, but we felt like we did something good for the children. And it provides insight for others that there’s value here.”

He and Dr. Noritz, however, emphasize that each initiative must be tailored to the center and ACO involved, because all differ.

Nationwide Children’s is now exploring how to bring this kind of care coordination to children covered by private health insurance.

Reference:

Noritz G, Roldan D, Wheeler TA, Conkol K, Brilli RJ, Barnard J, Gleeson S. A population intervention to improve outcomes in children with medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2017 Jan;139(1):(e20153076).

Image credit: Nationwide Children’s

About the author

-

Kevin Mayhoodhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/kevin-mayhood/

-

Kevin Mayhoodhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/kevin-mayhood/April 25, 2015

-

Kevin Mayhoodhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/kevin-mayhood/April 25, 2015

-

Kevin Mayhoodhttps://pediatricsnationwide.org/author/kevin-mayhood/April 25, 2015

- Posted In:

- Features